What is a Moral Imperative in Education?

Answering the question, “What is a moral imperative in education?” requires us to think deeply about our responsibilities as educators and the consequences of our choices.

While the stakes in education rarely involve life-or-death scenarios, the decisions we make profoundly shape the futures of the children entrusted to our care.

The Nature of Moral Imperatives

To explore the question of what a moral imperative is, consider a dramatic scenario: imagine rescuing a child from imminent danger, only to have your actions result in unintended harm to others.

Are we responsible for the unintended consequences of morally justifiable actions?

This question lies at the heart of understanding what is a moral imperative in any context, including education.

Michael Fullan, a prolific author on educational leadership and change, recognized that educating children involves a moral imperative—a recognition so central to his work that he used the phrase in the titles of two of his books.

However, Fullan never clearly defined what he meant by this term, leaving educators to puzzle over its precise meaning.

Clearing Up Confusion About Morality

Before we can fully engage with what a moral imperative in education is, we must address common misconceptions about morality itself.

First, morality is not synonymous with religion. Scientific research confirms that humans were moral beings long before organized religions existed, and we would remain so even without them.

Morality is a fundamental aspect of human nature, not a religious construct.

Second, morality is not simply about following rules.

Rather, morality involves imaginatively thinking through our understanding of a situation to arrive at a course of action that best ensures the well-being of those affected by our decisions.

This understanding draws from the work of scholars like George Lakoff, Mark Johnson, Owen Flanagan, Jonathan Haidt, and others who have studied the intersection of science and ethics.

What Science Reveals About Human Flourishing

To understand the moral imperative in education, we can learn from scientific research on how people recover from negative events.

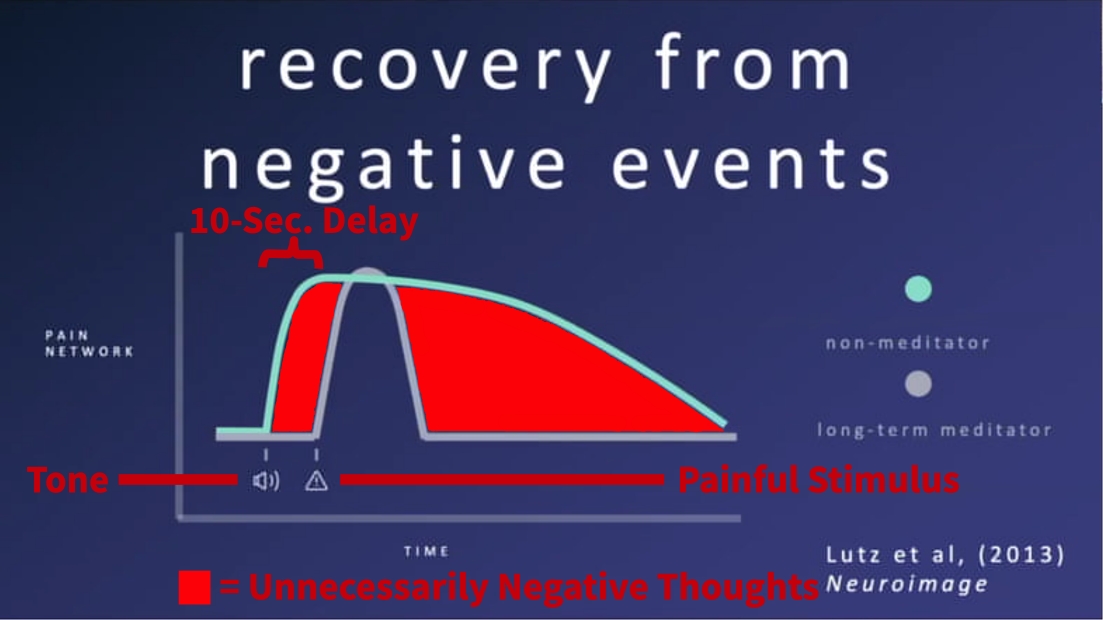

In one illuminating experiment, researchers compared brain activation patterns between long-term meditators and non-meditators when exposed to a painful stimulus.

The findings were remarkable. When a tone signaled an upcoming painful stimulus, non-meditators showed anticipatory activation in their brain's pain network—they were already suffering before the pain arrived.

Meditators, however, maintained their baseline state. When the actual pain occurred, both groups experienced it similarly.

But afterward, meditators recovered to their baseline rapidly, while non-meditators lingered in their pain response much longer.

This experiment reveals something crucial about education.

The difference between the two groups lies not in the pain itself but in the unnecessary negative thoughts that anticipate or dwell on painful experiences.

These thoughts extend suffering beyond what reality requires and weaken our grasp on reality itself.

Defining an Educated Person

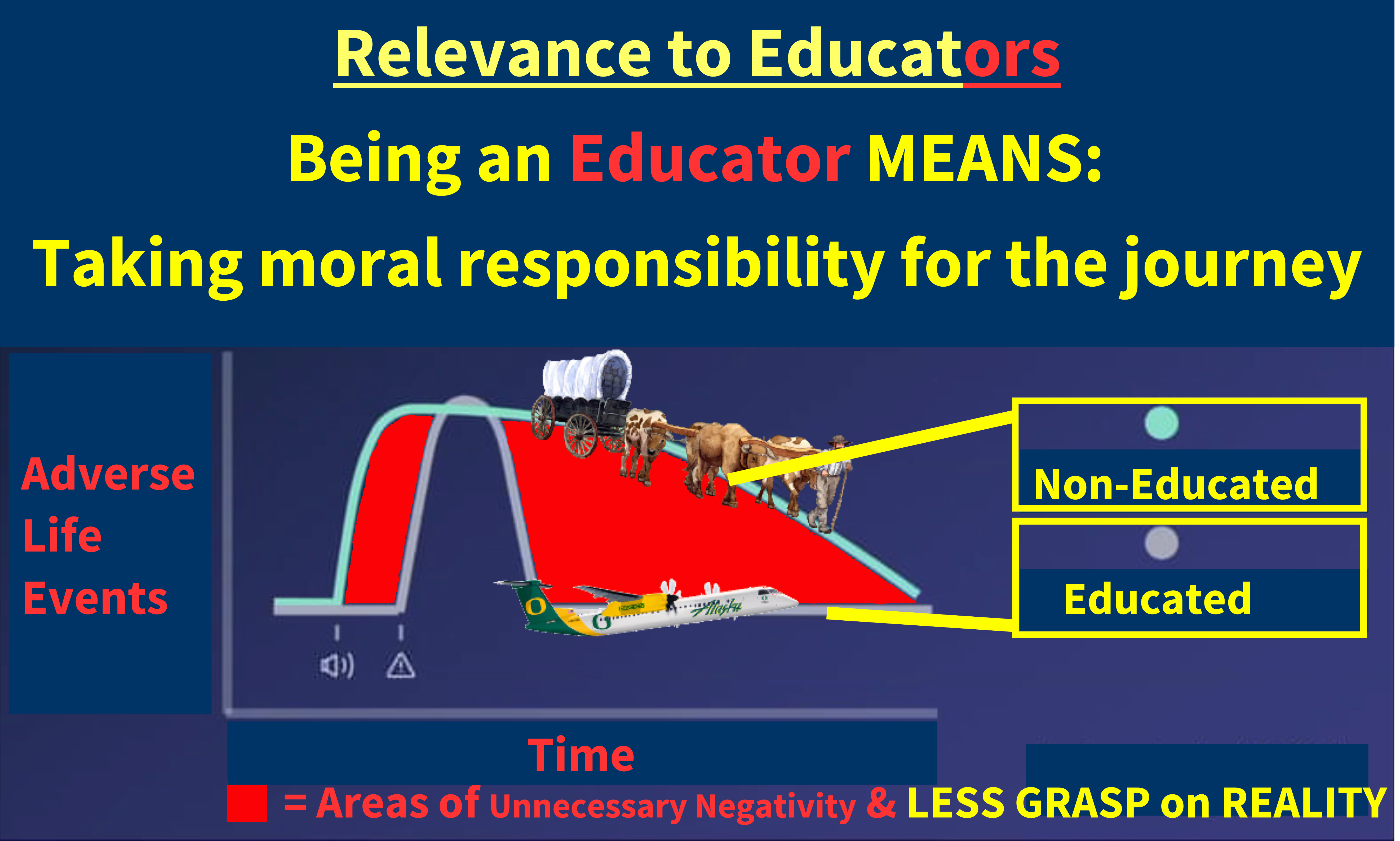

An educated person perceives accurately, thinks clearly, and acts effectively on self-selected goals and aspirations relevant to their situation.

When adverse life events occur, an educated person navigates the negativity like anyone else but recovers more quickly, maintaining a better grasp of reality throughout.

This understanding transforms how we answer the question of, “what is a moral imperative in education.”

Being an educator means taking moral responsibility for ensuring that each student's life journey is less negative than it otherwise could have been.

We are responsible for ensuring our students develop a better grasp of reality through the experiences we co-create with them.

Four Psychological Powers

To fulfill this moral imperative, educators must help students develop four essential psychological powers:

- Taming the monkey mind – Learning to quiet the restless, jumping thoughts that create unnecessary suffering

- Training the elephant spirit – Working with our powerful unconscious mind, which largely determines our immediate behavior

- Changing our current situation – Actively shaping the circumstances we find ourselves in

- Choosing different situations – Selecting environments that support our flourishing

Research consistently shows that situations are far more powerful than personality traits in determining behavior.

This means that choosing and shaping situations are our most powerful tools for growth.

Beyond Academics

If this is what education is truly about, where do academics fit?

Academic disciplines are helpful for thinking clearly and implicitly train the mind through structured situations.

However, academics alone are necessary but not sufficient for achieving the best possible grasp of reality.

To fulfill the moral imperative in education, educators must transcend academics.

This is difficult for many to accept, especially parents making life-changing decisions for their children.

The Oregon Trail Thought Experiment

Consider this scenario: You are in Independence, Missouri, on April 1, 1848, preparing to travel the Oregon Trail—a 2,200-mile journey taking four months on foot.

The risks are substantial: disease, hostile encounters, wild animals, and poor preparation could all prove fatal. Your odds of dying are one in ten.

Now imagine someone appears offering passage on an "airplane" that can complete the journey in one day with odds of dying reduced to less than one in one thousand.

The catch? You don't know when in the next four months this airplane will be available.

Which risk do you take?

This dilemma mirrors the choice facing parents and educators today.

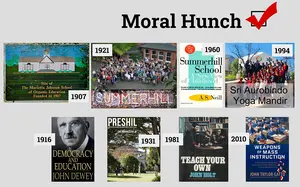

Alternative educational approaches have been shown to better motivate and engage students, providing a better journey with better odds of success.

Yet these approaches are unfamiliar and lack cultural support.

Meanwhile, mainstream schooling is well-known and culturally supported, despite evidence that it provides a worse journey with worse outcomes for many.

Psychologically, most people choose the familiar route with cultural support rather than risk the unfamiliar, even when evidence suggests the unfamiliar path is better.

They may rationalize that their child will beat the odds, but this reasoning typically follows the decision rather than preceding it.

Responding Wisely to the Question, "What is a moral imperative in education?”

Parents and policymakers act with urgency when making educational decisions, believing they are taking noble steps toward ensuring children's well-being.

Yet they often default to perpetuating a system centered on academics that produces harmful journeys for most students and fails to deliver educational outcomes as reliably as it could.

So, how should we answer the question, "What is a moral imperative in education?”

The question ultimately calls us to transform the education system from one that values academics over governance to one that does the opposite.

Ultimately, it means enabling students to develop a solid grasp of reality so they can flourish in whatever situations life presents—whether forced upon them or chosen.

The term "catalytic pedagogy" describes schooling practices that properly value governance and produce greater motivation and engagement in both students and teachers.

This approach represents a thoughtful response to the moral imperative in education—one that considers consequences carefully rather than reacting impulsively to immediate pressures.

When we take time to explore what a moral imperative in education is, we position ourselves to make decisions that truly serve our students' long-term flourishing rather than simply responding to cultural expectations or familiar patterns.

This is the challenge and the calling of education today.

Resources:

Lutz, A., McFarlin, D. R., Perlman, D. M., Salomons, T. V., & Davidson, R. J. (2013). Altered anterior insula activation during anticipation and experience of painful stimuli in expert meditators. NeuroImage, 64(64C), 538–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.09.030

Visual Explanations of the Lutz Study: Graph Explained & Brain Images from Mission Joy Film (IMDb Page)

Michael Fullan's Books: The Moral Imperative of School Leadership & Moral Imperative Realized

This article was printed from HolisticEquity.com