Introducing Catalytic Pedagogy:

Better Schooling for More Children

Introducing Catalytic Pedagogy - a revolutionary way to bring K-12 schooling into the 21st century!

I’m Don Berg and I designed this innovative school approach to create an optimal learning environment for students and teachers alike.

With a clear focus on deeper learning rather than simplistic knowledge delivery, catalytic pedagogy aims to reduce the amount of energy teachers must expend on activating the motivations of students before, during, and after instruction.

This approach will also enhance equity in classrooms anywhere in the world.

By combining elements of proven practical models (such as Democratic Schools, Comer Schools, and Montessori systems among others) with innovative strategies, such enabling students to opt into classes, we can measure increased engagement patterns in our learners.

Catalytic pedagogy is rooted firmly in psychology while drawing an analogy with chemical catalysis, meaning that instruction will become more efficient because the motivational energies of students and teachers will be more focused enabling them to waste less time.

By respecting students and teachers as autonomous agents who willingly engage with their reality we can inspire the deeper learning and academic achievement that we need right now.

Catalytic pedagogy is an innovative perspective on how to achieve precision tailoring of learning experiences for each student's needs at scale!

On this site you will find lots of videos and essays that are both explanatory and critical.

You will also find variety of tools to ensure that teachers can learn how to better engage their students and how to embed the psychology of learning in policy so that policy stops undermining the learning.

The essay below takes a deeper dive into the idea of catalytic pedagogy.

Enjoy,

Don Berg

Introducing Catalytic Pedagogy Essay & Resource Links

This is an introduction to catalytic pedagogy, which a new term to describe K-12 schooling options that work better for more children.

Before I explain my terminology in more detail I want to point out that bad schooling fails to do the job we, as a society, expect it to do because of how a pervasive misconception about learning interacts with the variety of historical accidents that gave us the mainstream school system we have today.

That misconception is that education consists of teachers delivering knowledge, skills, and information into the heads of students.

That false idea is the source of lots of the intuitions that guide many people’s decisions about how schools should operate.

Take the notion of Back-to-Basics 1.0 that arose in the 60’s and 70’s here in the USA, which seemed to be based on nostalgia for a fantasy version of the schooling of old.

Back to Basics 1.0 had three core elements:

1. Deliver the 3R’s of academics, meaning teachers should drill children on reading, ‘riting, & ‘rithmetic.

2. There should be no nonsense in the classroom, meaning not to waste time or money on arts, sports, or social services, but more testing is fine to ensure that the deliveries were made.

3. The classroom should be characterized by strict discipline meaning that the children must demonstrate absolute obedience to authority.

This model has significantly contributed to the pervasive pattern of disengagement that is characteristic of mainstream schooling worldwide, which is merely a symptom of the deterioration of the psychological well-being of children which has recently been getting more attention.

I label it 1.0 because I propose a new version of what counts as basic.

Back-to-Basics 2.0 is derived from the psychology of learning, rather than a nostalgic fantasy.

The delivery metaphor is wrong; it is more accurate to say that the teachers inspire the students to mentally re-construct their map of reality.

The most important feature of an educational experience in this new way of thinking about schooling is the agency of the learner.

Academics are reduced to being merely one of many tools that can be used by a learner to express their agency.

Back-to-Basics 2.0 is a three-step strategic plan for creating a systemic approach to inspiring students en masse, or to be more precise, for ensuring that any school can achieve catalytic pedagogy.

1. Teach governance before academics, meaning that the organization of the school must emphasize self-management over bureaucratic compliance.

2. Manage for engagement, meaning that the school must ensure the students are actively involved in making important decisions about their learning, not just following arbitrary or pre-determined pathways defined and constructed by anonymous bureaucrats.

3. Improve citizenship with need support, meaning that when behavior is counterproductive the school must provide more psychological support, not less.

So, let’s dive into what it means to call a pedagogy catalytic.

Catalytic Pedagogy: Catalysis Literally

Catalysis is a term from chemistry.

“Catalytic” refers to how some chemicals make the reactions between other chemicals faster, more energy efficient, and less wasteful.

And the remarkable thing about the catalyst is that in the end it remains unchanged and can do the same process all over again.

What I am proposing is that we educators can be more efficient and effective during the process of instructing children by creating certain conditions around the instructional process.

But let’s start at the beginning with a more detailed account of the literal version of catalysis.

A catalyst is something which speeds up a chemical reaction but at the end of the reaction has the same mass as it had at the beginning of the reaction.

This means that it is not used up.

A catalyst works by providing an alternative pathway for the reaction to occur.

This alternative pathway has a lower activation energy than the pathway without the catalyst.

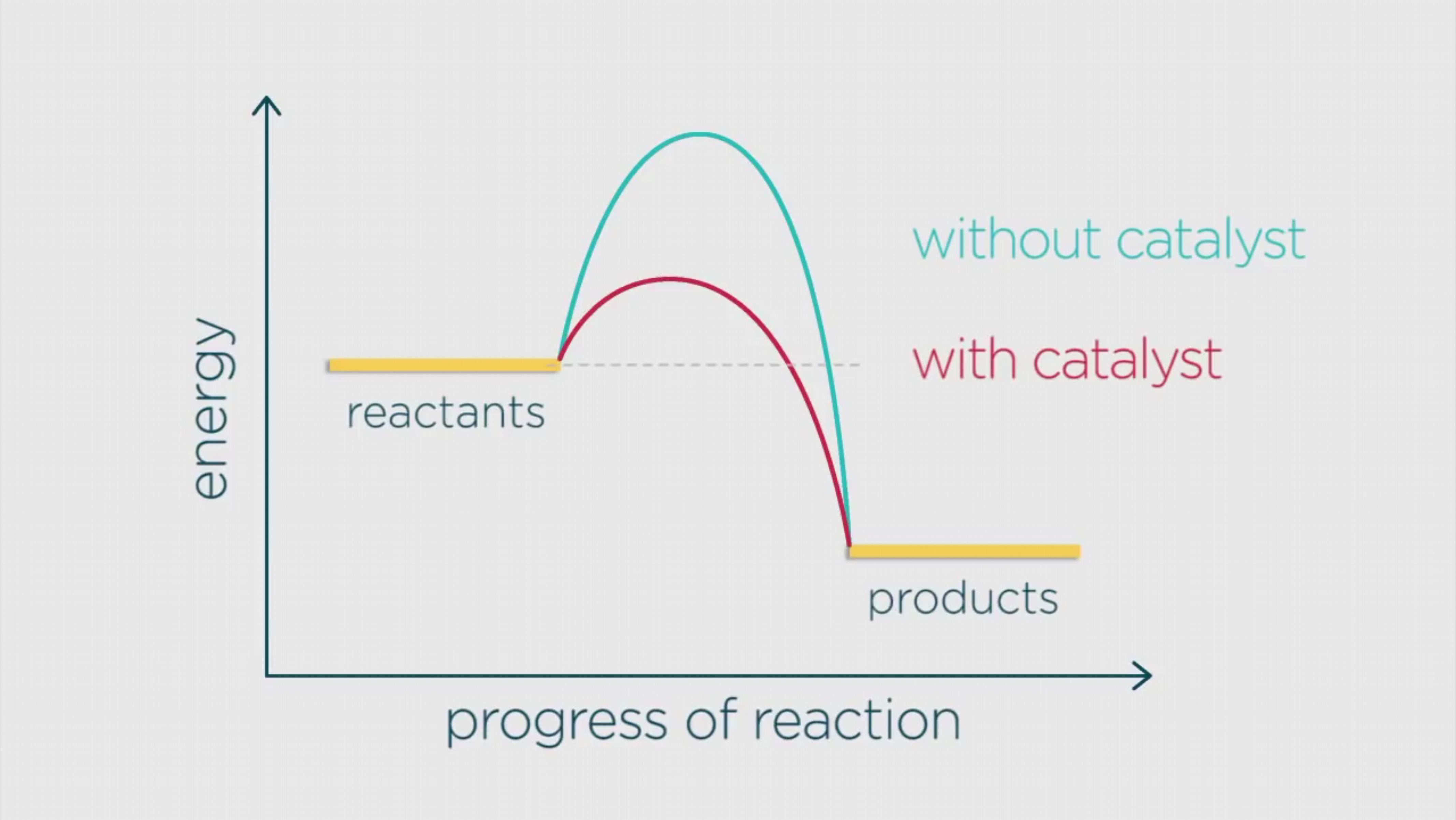

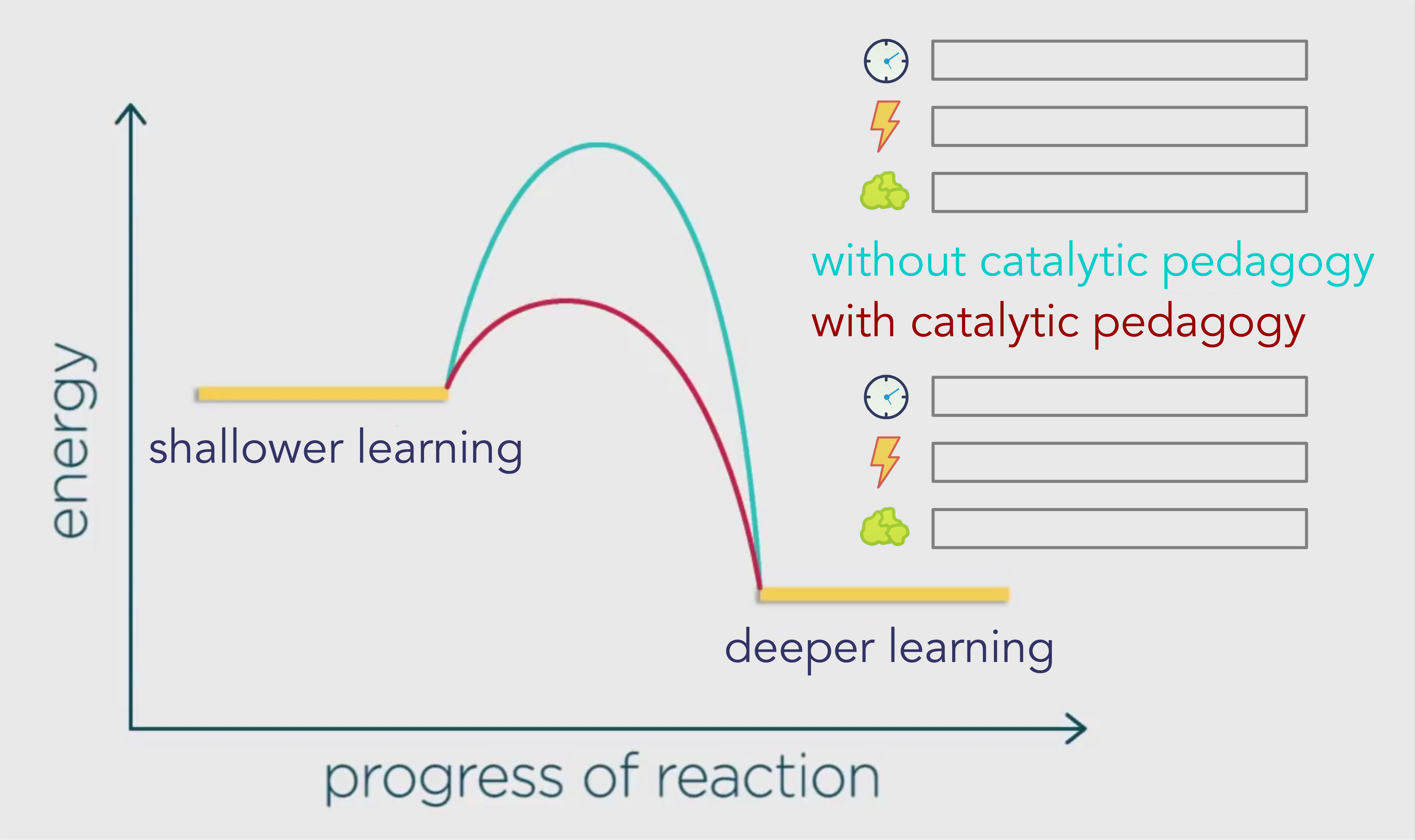

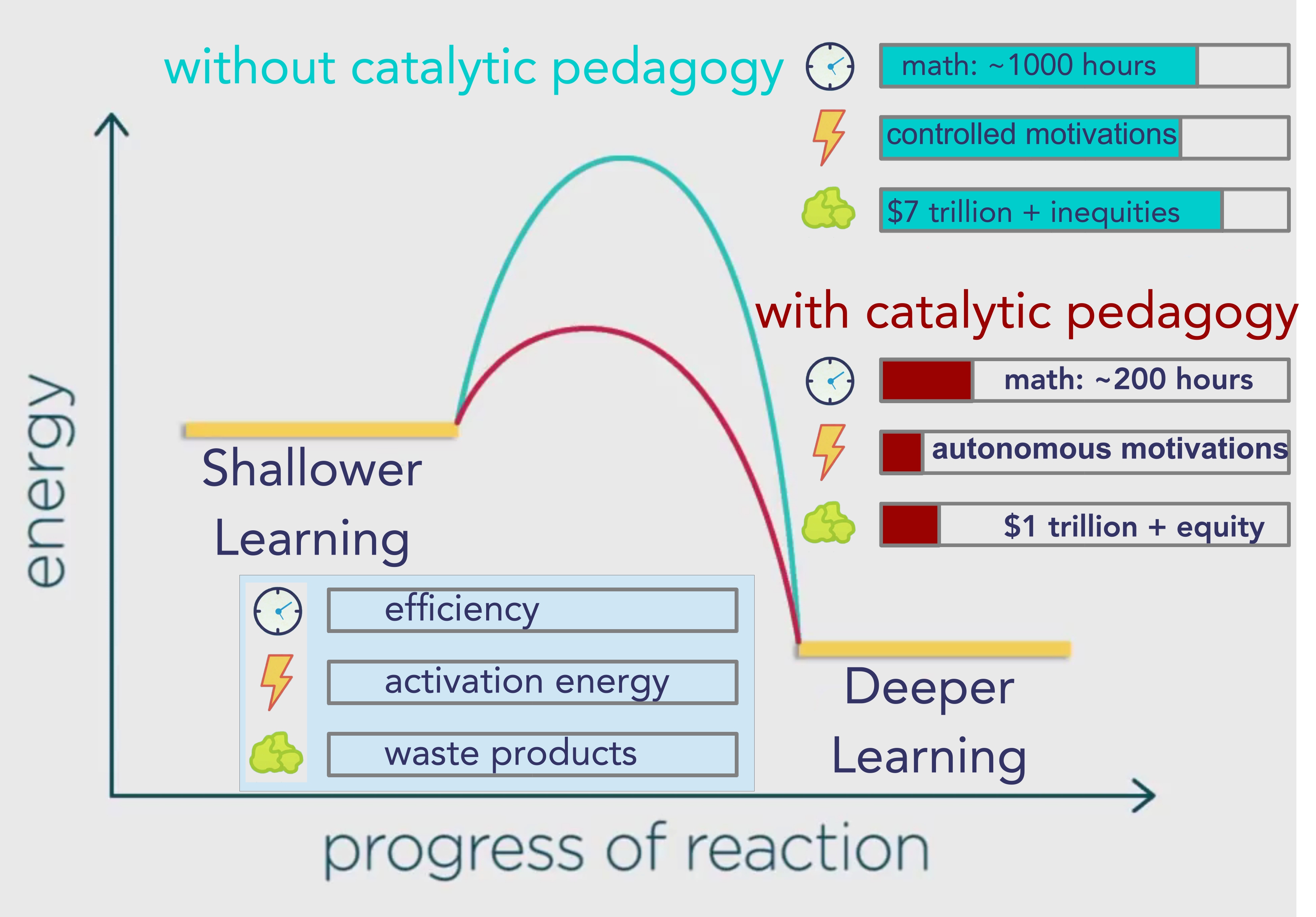

Below is a diagram showing two pathways for a reaction.

The blue pathway is the energy profile for the reaction without the catalyst, and the red pathway is the energy profile for the reaction with the catalyst.

You can see that with the catalyst, the activation energy is lower.

As a result of the activation energy being lower, there are more molecules with the required activation energy, and so more fruitful collisions occur per second, and hence, the reaction is faster.

Catalytic reactions also produce less waste since the catalyst can be used repeatedly.

Catalytic Pedagogy: Building the Analogy

Below is the graph again, except instead of showing the reactants and products, we are looking at how students go from their default shallow learning into deeper learning.

The reaction we are considering is the students’ reactions to instruction.

Remember that this process happens at some slow rate independent of what we do because human beings are inherently curious about their world and how it works.

Inherent curiosity creates a low level baseline rate, but it is slow, inefficient, and wasteful.

This describes the default operation of mainstream schooling in which a bunch of children are arbitrarily assigned to classrooms without having the option to opt out of the instruction that will be provided there.

Let’s examine those three key aspects of reactions: activation energy (lightning bolt), efficiency (clock face), and waste products (crumpled wad of green paper).

Only now we are focusing on children’s reactions to instruction.

The blue pathway is showing us the activation energy required without catalytic pedagogy, as in mainstream schools.

The red pathway shows us the activation energy required with catalytic pedagogy which is going to result in different rates of energy, efficiency, and waste in alternative types of schooling.

Catalytic Pedagogy: The Waste Component

Let’s start and end with waste.

The most important waste to consider in education comes from the epidemic of disengagement that has been well documented in both schools and the workplace, even though it gets very little attention in the media.

For instance, according to Gallup, 70% of teachers report being disengaged.

In the introduction of my award-wining book Schooling for Holistic Equity, I suggest we can be confident that students are also disengaged at a rate of about fifty to seventy percent, based on a combination of expert estimations and direct surveys.

It is not a stretch to assume that the habits learned in school have an effect on later workplace patterns.

If the pattern carries over then it makes sense of the fact that Gallup reports the average rate of disengagement in the workplace globally is also 70%.

Gallup estimates that workplace disengagement is costing the global economy about $7 trillion per year.

Plus, a 2015 report from the Carnegie Foundation called “Motivation Matters” pointed out that in the USA there is an engagement gap just like there is an achievement gap between minority and majority students.

They also noted that the engagement gap is the more solvable problem of the two.

Catalytic Pedagogy: The Activation Energy Component

Next we want to consider activation energy, which I will take to be the role of motivation.

In reviewing prior studies for my thesis I discovered that about thirty years of research in mainstream schools found that the intrinsic motivation and engagement of students declined within each year and over the course of the years through high school graduation.

The preferable term for the entire group of the less desirable more external motivations is “controlled motivations,” so I take it that mainstream schooling produces a lot of controlled motivations.

My published thesis research was about the patterns of intrinsic motivation for students in two schools where instruction is an opt-in for students, the only courses they took were ones that they chose to take.

It should come as no surprise that when children actively choose to take a class they have a better chance of engaging more productively with it.

What I found was that these schools maintain the intrinsic motivation of their students across the years, which is consistent with just a couple of other studies of engagement in similarly alternative schools.

While I looked specifically at intrinsic motivation, the entire group of more desirable internal motivations is called “autonomous.”

These alternative schools support autonomous motivations in their students by being organized to give children the opportunity to opt-into classes.

This means the instructors expend much less energy getting students activated for making productive use of the instruction they receive.

The number of productive instructional collisions increases.

Putting it this way makes an important distinction between productive and unproductive instructional collisions.

Just because a student has an instructional collision with an instructor in a classroom does not mean that it was an educationally productive incident.

And we cannot always tell the difference between productive and unproductive when the teacher gives the student a passing grade just for having a collision.

When grades and test scores reflect educationally unproductive collisions I call that fauxcheivement, or fake achievement.

I have never met anyone who was successful as a student in mainstream classrooms who did not agree that at least part of the time their success depended on jumping through the hoops, or just going through the motions, without learning the lessons taught.

Catalytic Pedagogy: The Efficiency Component

Now, we turn to efficiency.

In this case you need to know that the State of Massachusetts, USA, compels children in the first through sixth grades to attend 180 days of school each year.

Let’s estimate that they will receive about an hour a day of math for those six years, which means that those State public schools expect to take somewhere near a thousand hours to deliver that math curriculum.

Now consider that Daniel Greenberg, who was one of the co-founders of the Sudbury Valley School in Framingham, Massachusetts, taught math for many decades.

He taught the first through sixth grade math curriculum.

Now you also need to understand that all instruction at Sudbury Valley School is completely optional for all students ranging in age from five to eighteen years old.

In this case he taught the entire first through sixth grade math curriculum with one hour a week of direct instruction with lots of homework over the course of just twenty weeks.

He accomplished in 20 hours what the State of Massachusetts expected to take around a thousand.

That is a much more efficient use of the instructional expertise that a teacher has to offer.

But let’s assume that Daniel Greenberg was an exceptional instructor and that when we take catalytic pedagogy to scale we will get ten times less of an efficiency gain than he claimed, so let estimate basic math will take two hundred hours.

That’s still eighty percent less than a thousand, so I’d say it’s a worthwhile gain.

The Meaning of Catalytic Pedagogy

The problem we have right now in the education system is that the mainstream of schooling is too slow to produce the deeper learning that we as a society need to meet the demands of our complex technological age.

Without catalytic pedagogy the amount of energy that we expend to maintain the current rate of student reactions to instruction is too high, the process is too slow, and there are too many waste products.

When we add catalytic pedagogy the activation energy is lower, the process is much faster, and there are going to be fewer waste products.

However, I don’t really know how much money we could save, let’s assume that other factors will still cause a trillion in waste.

Seems to me that reducing the waste is worthwhile in any case, but perhaps more important is that I do know that it will bring about much more equity.

The whole phrase “catalytic pedagogy” refers to the context surrounding instruction that schools use to produce more autonomous motivations and more fully engage their students and teachers in instruction.

Making students opt-into classes is one way that can happen, but it is probably not the only way.

There are promising models and practices under the terms deeper learning, democratic schools, rights respecting schools, Comer schools, Montessori, and probably others.

In order for this view of pedagogy to become more prevalent it will be necessary to make regular measurements of the patterns of motivation and the quality of engagement in schools.

I explain catalytic pedagogy and Back-to-Basics 2.0 in more detail in my award-winning book Schooling for Holistic Equity: How to manage the hidden curriculum for K-12.

For a more concise book on my perspective I recommend The Agentic Schools Manifesto which is where I articulate the case for agency as the central factor in education.

If you are curious about the Back-to-Basics 2.0 strategy that I mentioned at the beginning then check out my video called Definition Of Education: A Literal Core which you can find under the Philosophy tab.

If you are concerned that my emphasis on equity could bring about a horror show of unintended consequences I suggest that you check out my video about the difference between equity and equality, under the Equity tab, in which I suggest how to prevent those unintended consequences.

This article was printed from HolisticEquity.com