How Education Policy is Maintaining a Market Failure in K-12

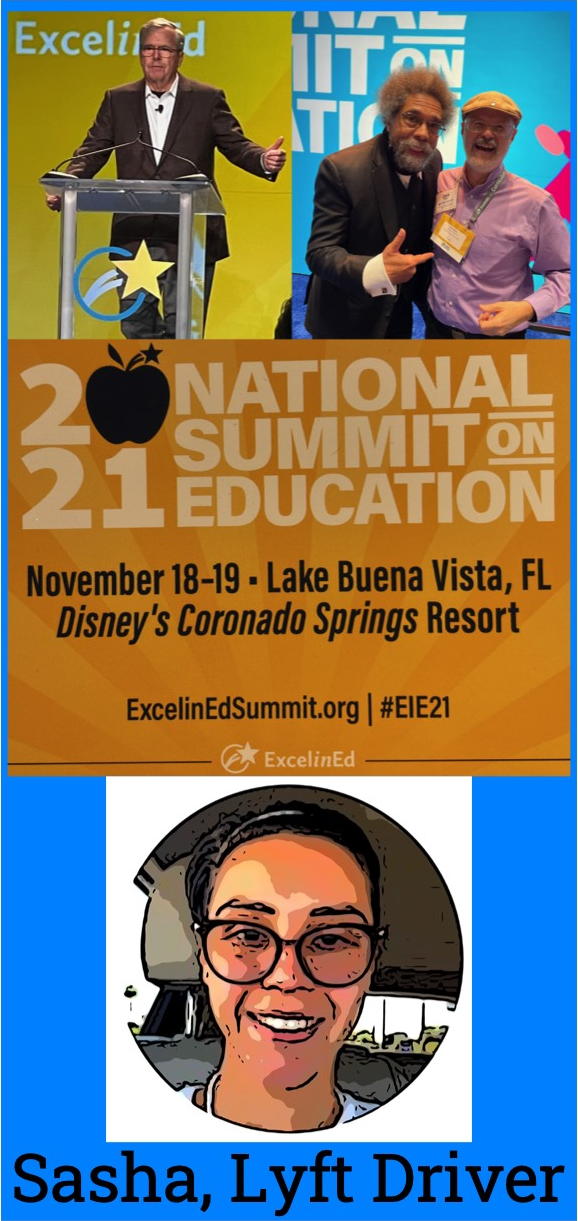

The effects of education policy on families was brought home to me once during a Lyft ride.

My partner and I were in Orlando for the ExcelinEd conference and had taken a few extra days to rest and recreate.

At the end of our trip, as we were heading to the airport, we got to talking to our Lyft driver, Sasha.

We mentioned that we were heading home to Oregon.

She explained how her oldest son, a high schooler, was in Oregon staying with his father.

She sent him there because he was having a hard time being an obedient student in school.

We commiserated with her about the challenges that high school presents to teenagers.

In order to encapsulate my view of schools I said, “Imagine that you are driving your car but instead of having the gas gauge connected to the fuel tank it was connected to the wiper fluid, instead.

“That would be difficult, wouldn’t it?

“That is how our schools are operating; education policy makes them measure the wrong things.

“That makes the job that teachers are trying to do a lot more difficult than it needs to be.”

She was relieved to know that we understood the problem.

When we arrived at the airport she became energized as we encouraged her to search out people who had already pursued her secret ambition to try world schooling, which is basically home schooling while traveling.

Education Policy Neglects Agency Data

It is obvious that we need to give school managers the information they need to make K-12 schools into more reliable mechanisms for producing the educative outcomes we all want.

Everyone knows need satisfaction, motivation and engagement (which we will collectively call agency) have some role to play.

Everyone is clear that getting from one place to another, educationally, requires those things.

The problem is not that the school system fails to recognize that fuel (agency) is essential.

While seeing the road is obviously important, running out of wiper fluid is a far less impactful problem than running out of gas.

But, the school system is overvaluing academic information (the wiper fluid level) by failing to collect the agency data (the fuel level) that would provide for better management.

Based on policy dictates at both state and federal levels, high school or college graduation are the most important goals for our school system.

The system writ-large currently does not care whether the learning that happened along the way was shallow or deep.

There is no quality control over the process of getting students to those graduation goals.

It only matters that the arbitrary standards of academic bookkeeping were satisfied.

(If you are provoked by my calling them “arbitrary,” please, read chapter 14 of my book Schooling for Holistic Equity and get back to me about why I’m wrong.)

To be generous, let’s assume that the advocates of this status quo have not yet realized that appropriate measures are now available that can provide us with useful checks on the quality that we need.

I will argue that the school system is a type of market for data, but that data market is failing because it overvalues academic data and undervalues agency data.

The pattern is hard to change because the failures that result have come to be considered normal.

The task of changing the system must overcome that normalization process in order to create a market correction.

Education Policy is a Big Deal for Individuals Like Sasha AND for Society

The negative consequences of training children to normalize poor motivation and DISengagement across the globe everyday are costing us trillions of dollars every year, according to Gallup (Harter, 2017).

Those trillions of dollars indicate that current education policies have created a massive market failure.

It is a kind of market bubble that places an absurdly high value on academic data and places no value on agency data.

Because Sasha’s son was not able to sit still and obey the arbitrary dictates to produce academic data, powerful psychiatric medications were prescribed.

She said that being medicated made him, “a zombie at school and a terror at home.”

She made the difficult decision to change his environment to better suit him rather than continue to submit to a regimen designed to change him to suit the environment.

In Oregon he found new opportunities that seemed to be helping him to better manage his life, so Sasha probably made the right decision.

If the school folks and Sasha had agency data available as a matter of education policy, the recommendations and decisions would probably have been a lot different.

It would have been clear that the school could have done more to support her son, and even if his diagnosis may have remained, a larger variety of methods for providing non-pharmaceutical support would have been clearly indicated.

Better Education Policy?

How can education policy create better situations for students like Sasha’s son?

To borrow the title of a recent best-selling book by Jonathan Haidt; How can we calm The Anxious Generation [[URL]]?

First, we have to recognize that the problems are more with system-level education policy than with how people choose to behave in their current situation, which those policies created.

From a psychological perspective I recognize that we all have an illusion about how much control we have over our own behavior.

You and I both have a clear and abiding sense that we could choose differently than we do in any given moment.

What we consistently fail to recognize is how powerfully the situation in which we are making our choice affects each behavior we choose.

It is trivially true that we can make choices moment-to-moment.

What is deeply true, and often disturbing, is how little power we actually exert to counteract the forces that guide us to the particular choices we end up making.

There is a book called Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds that documented numerous examples of how regular people get caught up in what, in hindsight, seem like outrageous economic and social patterns.

We almost never notice how a situation constrains the range of choices we consider to be possible.

Systems are always far more powerful than our intuitions give them credit for being, and the system defined by education policy is notoriously powerful.

The Economic System, For Example

Let’s take a moment to appreciate that there is an arena in which we readily recognize these kinds of systemic effects: our economy.

We still have lots of delusional ideas about it, but at least there is a regular stream of data and storytelling about how it is operating as a system writ-large.

We are regularly subjected to opinions about how the economy is faring and leaders regularly make recommendations about how to manipulate those patterns.

Like all of us, they project far more confidence in their own powers than the data suggest they actually have.

But when they pull on economic levers, they are operating on a scale that has bigger consequences, both good and bad.

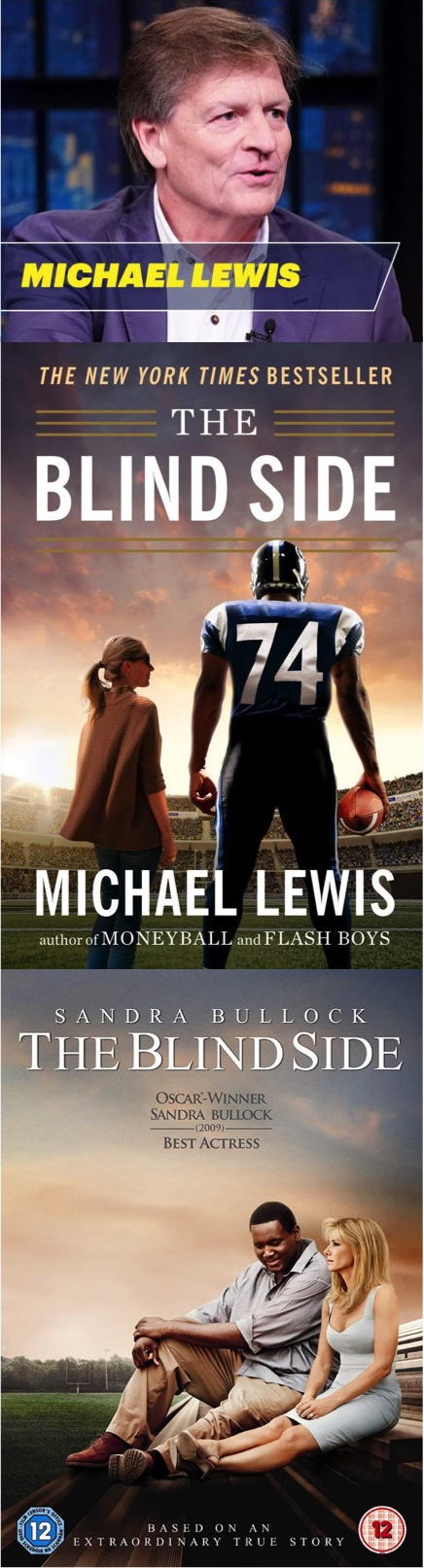

Transformation of Markets According to Michael Lewis

Let’s consider how markets, as a major component of the economy, are transformed.

The financial journalist Michael Lewis has written many great books about how markets are transformed.

He started off his career writing about market transformations that he, as a bond trader for Salomon Brothers in the 1980’s, witnessed directly.

His books about the transformations of the markets for sports talent, Moneyball and The Blind Side, have both been bestsellers and made into good movies.

In Michael Lewis’ stories of market transformation, the essential foundation is how the invisible hand of the market was, pre-transformation, doing a terrible job setting prices for assets and the level of risk that those prices implied.

Those investors who could more accurately evaluate the risk of those assets were in a position to get great pay-offs during the market correction of those wacky prices.

Moneyball: The Art Of Winning An Unfair Game (Lewis, 2004) is about how professional baseball players with a better than average ability to get on base were undervalued.

That market condition held true until the manager of one of the poorest teams in the league, the Oakland A’s, hired an economist who could discover more valuable prospective players using on-base percentage to filter the data.

The amazing results spoke for themselves and the market for players was transformed as a result.

In The Blind Side: The Evolution Of A Game (Lewis, 2006) the asset under consideration was left tackles in football.

They are the guys who protect the quarterback from being attacked on the side he can’t see while throwing.

In education policy academic data is being systematically overvalued while motivation and engagement are being systematically undervalued as key components of deeper learning, which is fundamental to effective education.

The next critical piece of the market transformation puzzle is someone who has both the information and the opportunity to act on that information about the market’s dysfunction.

In Moneyball, the person who could act was Billy Beane the manager of the Oakland A’s.

In The Blind Side, there were several people who took action, but the central character Lewis focused on, for the market transformation part of the story, was the coach Bill Walsh.

Decades before the action in the main storyline regarding the football player Michael Oher, Walsh had been an instrumental force for transforming the passing offense into a more reliable means of getting the ball down the field.

It was in the context of that already transformed market that Michael Oher was an unlikely person to have become an accomplished professional player.

The book is an argument that being a poor Black kid in a harsh urban setting made Michael Oher an asset that our society would usually have overlooked.

We do not have a reliable system for searching through the population of the urban poor for marketable talent.

Michael Oher’s marketability changed radically due to the particular chain of events recounted in the book.

When he was taken in by his white, well-connected, and sports-involved adoptive family, his access to the market changed so that he had the good fortune to extract from that market a lot of value in the forms of exceptional college and professional football careers.

In the education context there is a major market failure because education policy has systematically undervalued the roles of motivation and engagement.

This undervaluation is demonstrated by the lack of measures for those qualities and ignorance of their potential efficacy and availability.

Due to education policies that established the academic focus in the 19th century, what is lacking in the market is a means of collecting and using school climate data that include measures of agency.

Transforming the Market for School Data

Accomplishing this market transformation is going to be challenging because there is a pervasive organizational dynamic working against it.

There is no shortage of media coverage of various educational disasters that occur on a regular basis.

The perennial reform movements are always pointing out inequities and problems.

The K-12 system has normalized a pattern of disasters and near-disasters.

The critics consistently use academic data to inform both their critiques and their proposals to create accountability.

They take the pervasive collection and dissemination of academic data to be perfectly normal and desirable.

There have been some small nods to school climate, which is the category that would include measures of agency, but never in a way that could challenge the supremacy of K-12 academic data.

As a management tool the most significant problem with academic data is that it is not actionable.

Academic data amounts to vanity metrics because they make leaders feel good when they see the data as favorable, but when they see them as unfavorable they fail to indicate specific, productive next steps.

The data paints a picture of success and failure, but when you are failing it is not sufficiently clear what to do to correct the problem.

And when you are succeeding it is equally unclear what you should do to maintain that success.

The persistent deterioration of mental health among students of all demographics across the globe makes it clear that the norms of school management encourage the willing sacrifice of student and teacher quality of life in order to maintain records of “performance.” (Gray, 2013; Calming the Anxious Generation)

The Risk of Fauxchievement

What has gone unacknowledged, though pervasively recognized, is the fact that achievement can be faked.

A true academic achievement is one in which a student and teacher grapple with the reality that underlies the academic subject area they are working on together.

When deeper learning occurs the student eventually grasps that reality with both more accuracy and the ability to achieve meaningful goals.

The student who attains a better grasp on reality has truly become more educated.

Improving a person’s grasp on reality is the only meaning worthy of the term “education.”

The marks of academic bookkeeping (grades, test scores, diplomas, etc.) are lame consolation prizes and have the pernicious effect of confusing actual educative outcomes with the marks that merely serve as administrivial indicators of obedience to systemic demands.

Those demands are made in the hope that educative outcomes might also result from that obedience.

The fact is that the adminstrivial bookkeeping can be attained by students independent of the deeper learning that is required to educate them.

Thus, the academic bookkeeping can easily reflect fauxchievements, rather than actual achievements.

The Dangers of Normalizing Risk-Taking

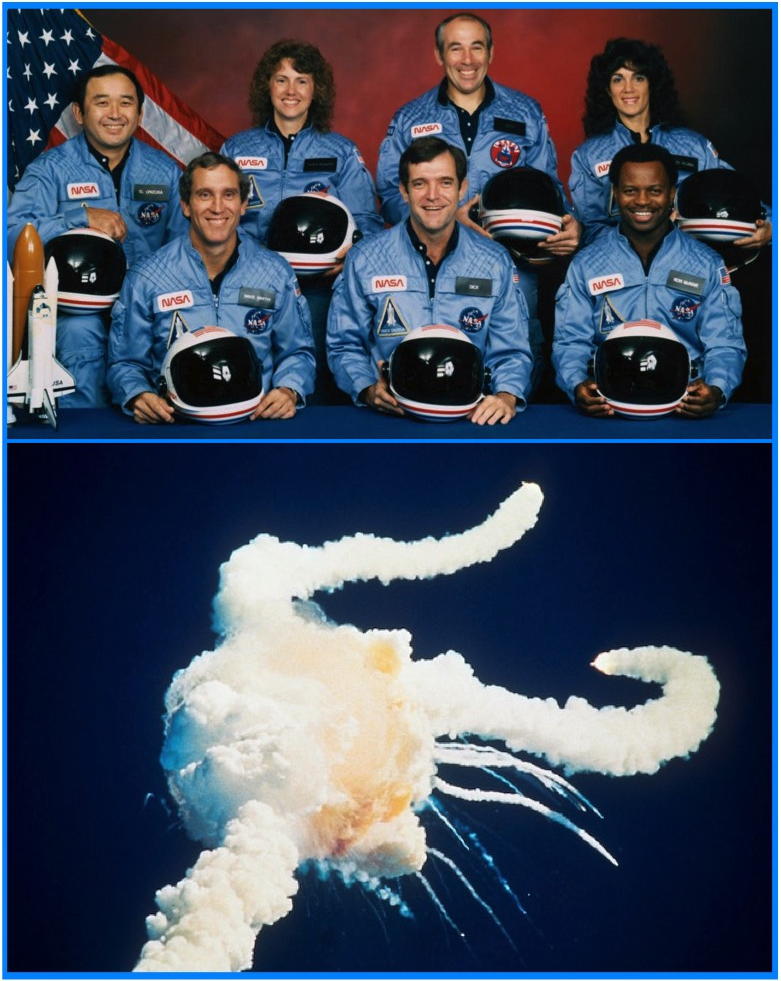

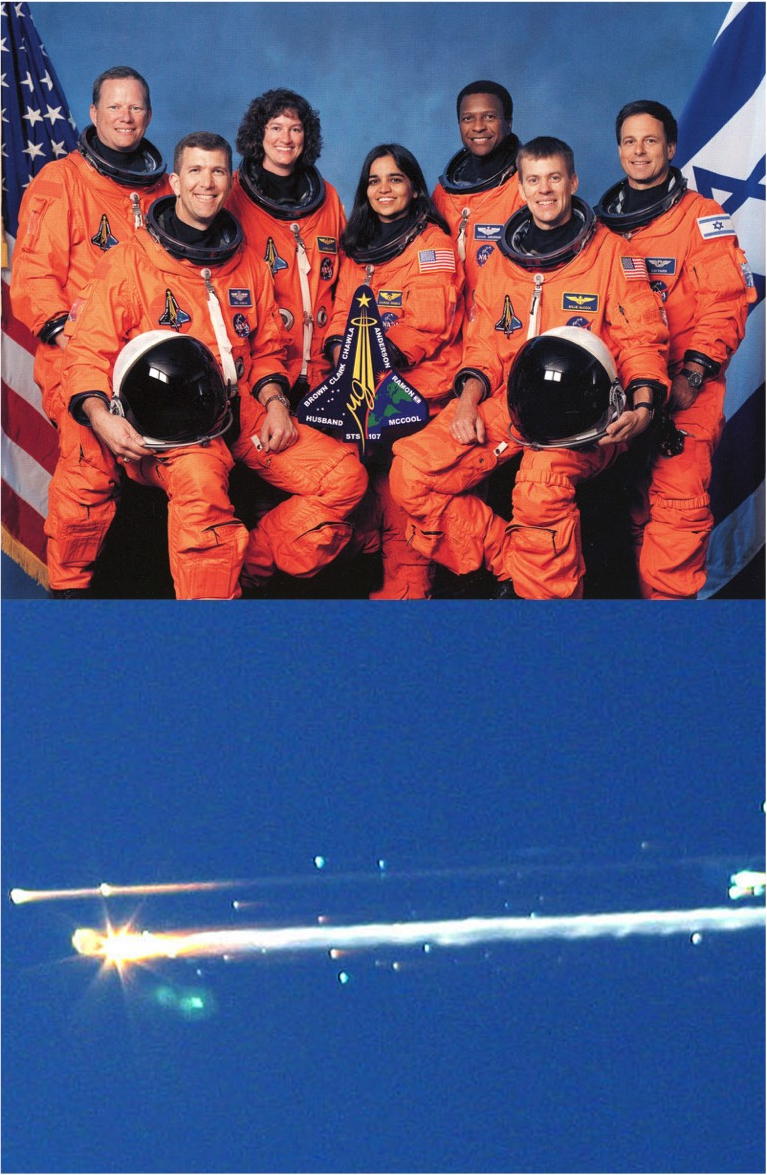

The normalization of fauxchievement is like the normalization of near disasters that preceded the deaths of fourteen Space Shuttle astronauts (Tinsley, Dillon, & Madsen, 2011; Feynman & Leighton, 1985).

The two times that the space shuttle was fatally destroyed, once on launch and the other on reentry into the atmosphere, were examples of the normalization of near misses.

In both cases, the system was demanding something other than the safety of the astronauts.

The first disaster was caused by the failure of a gasket in one of the booster rockets for the space shuttle Challenger.

The manufacturer had warned that the gaskets were susceptible to deterioration under certain conditions.

The gaskets were observed to have partially deteriorated on most of the prior launches.

But instead of valuing the safety of the astronauts the management system ended up “normalizing” the risks, rather than mitigating against them.

They saved on the cost of redesigning that component which would entail a massive redesign of the whole rocket; the risk of a catastrophic failure was minimized to the point that the “partial failures” were accepted as normal.

Instead of refusing to take those risks, which would require the courage to demand expensive changes, they accepted the risk as a normal feature of the system, which effectively doomed seven future astronauts.

That normalization made it possible for a whole series of decisions to be made causing the Challenger astronauts to die.

In the case of the Columbia disaster, ice falling off the main rocket engine during launch was normalized.

There was clear documentation that a piece of ice of sufficient size could strike the protective foam tiles on the leading edge of the shuttle’s wings with enough force to cause major damage.

Those tiles are the only barrier protecting the shuttle from the extremely high heat that is generated during re-entry into the atmosphere at high speed.

That normalization killed seven more astronauts.

The engineers and managers repeatedly recorded near-misses of disaster on many prior missions, but they took the same risk again and again.

Their “normalization” turned what had been many near-misses of disaster into an actual one.

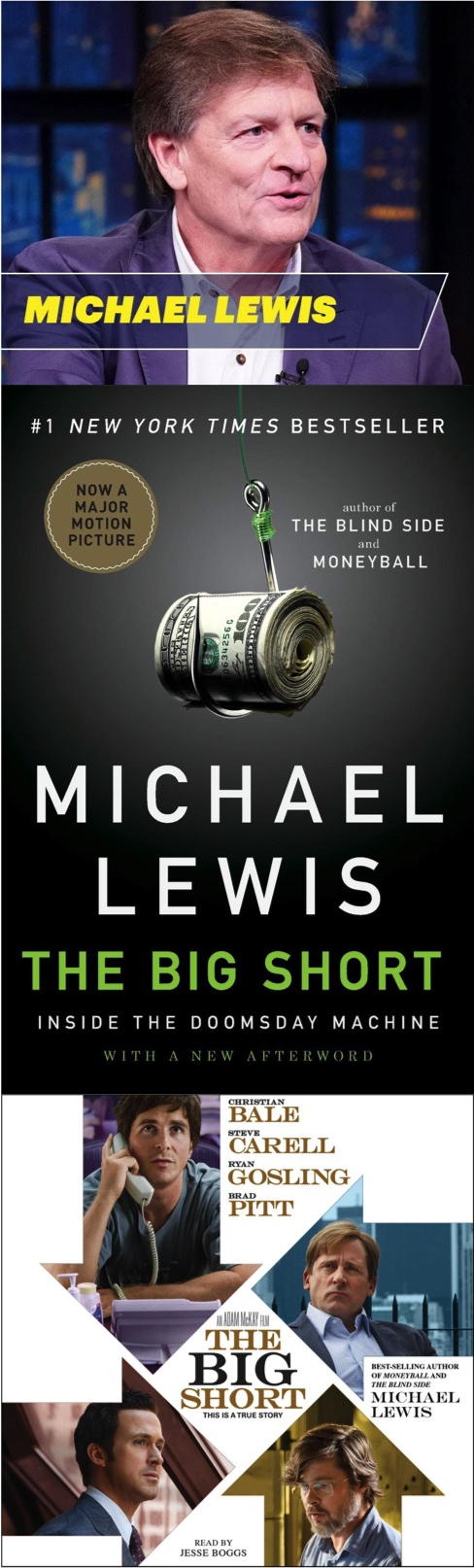

Returning to Michael Lewis’s reporting, we can also see the effects of normalization in the transformations of financial markets.

The financial disasters he recounted in his books Liar’s Poker and The Big Short (also made into a movie), were caused by this kind of normalization process.

Take a risk, observe that disaster did not happen, take the risk again.

Every time you take the risk without experiencing disaster make the delusional assumption that your “success” diminishes the risk.

The same process was at work at Enron.

The story of Enron’s disastrously criminal accounting in the book Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room by Bethany McLean and Peter Elkind, which was also made into a documentary film, indicates that the same process of normalization of unacceptable risks was at work.

According to research reported in an article for the Harvard Business Review in 2011 by Tinsley, Dillon, and Madsen, this kind of normalization of potentially catastrophic outcomes is the default for most organizations.

Countering the Normalization of Risk-Taking

How can it be countered, you ask?

It is normally countered in markets through pricing.

When a financial market is working properly the price of the various stocks, bonds, or other financial instruments reflect the risks that are being taken.

As a buyer you will normally pay more for safer bets and pay less for riskier bets.

But the assumed nature of a financial market is one in which you are also expected to become a seller at some future moment and in order for the risk “pay off” you must later be able to sell that asset for a price that will generate a profit.

In non-financial realms, normalization of risk is countered through organizational processes that enable the component individuals, employees, managers, board members, etc., to better grasp the reality of the situation that the organization faces.

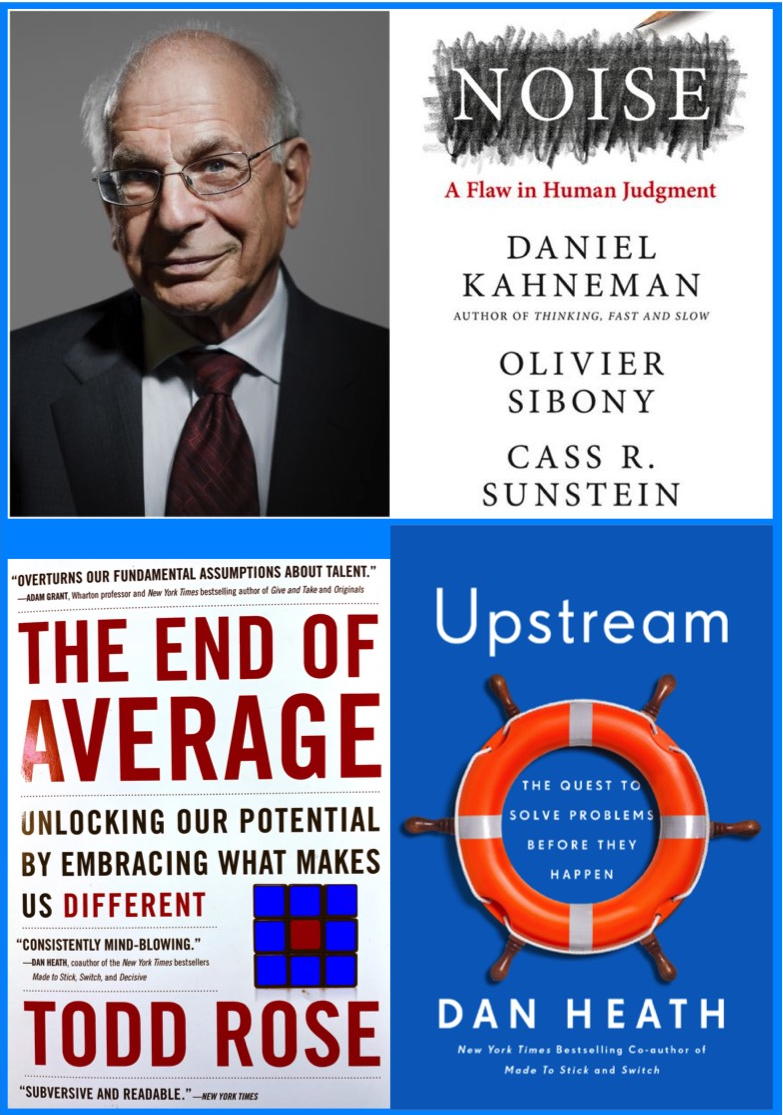

Recent books in this vein include Daniel Kahneman’s latest book Noise: The Flaw in Human Judgement (Kahneman, Sibony, & Sunstein, 2021), The End of Average: Unlocking Our Potential by Embracing What Makes Us Different by Todd Rose (2016), and Upstream: The Quest to Solve Problems Before They Happen by Dan Heath (2020).

In education I believe that countering the forces of normalization of the superiority of academic data will require a multi-stage effort.

First, there needs to be a literal market for the measures that produce the right kind of data, with both internally reported formative results that can be used immediately for improvement and summative results that can be reported elsewhere.

There need to be schools that demand it and providers who can supply measures for it.

Second, there needs to be a sustained campaign to argue for the relative importance of this very specific new kind of school climate data.

Finally, there will need to be education policy frameworks developed to enable the transition from the dominance of academic data to a new accountability regime.

The brave souls who want to try out the new management ideas need some legally binding protections from the old guard and especially from the potential wrath of parents who will inevitably lag behind the adoption curve.

Pay-Offs of Education Policy

In the space game the “pay off” in the short-term is astronauts who are alive and a working space shuttle.

Over the long-term you want the astronauts in those shuttles to continue to accomplish important tasks in space over many missions.

In sports the short-term “pay off” is winning games and the long-term pay off is attracting fans who are enthusiastically paying to see the winning happen.

In K-12 we need to see beyond the short-term “pay off” of graduating a student.

We need to become attuned to the quality of the experiences of both teachers and students.

In K-12 education policy we need to look to the long-term “pay off” of a citizen who has a systematically better grasp of reality.

We need citizens who are capable of making contributions that are valuable to them individually, to the organizations to which they belong, AND our society as a whole.

The pay off is Sasha’s son being encouraged to recognize that his ability to shift his attention more rapidly than most people has the potential to become a positive contribution to society.

He needs to realize that it is not a personal liability that should be medicated away.

The real pay-off is when we have a system in which all students engage enthusiastically with the passions that their teachers share with them which creates and maintains joyful schools.

The pay-off we’re working towards at Deeper Learning Advocates is schools managed to maximize student and teacher engagement, not managed for the production of grades, test scores, and diplomas that might make school management look good without producing truly educated citizens.

When schools are managed to maximize the engagement of students and teachers they are practicing what I call Catalytic Pedagogy.

Independent of what they may say about what they think they are doing, if a school produces the result of maximum engagement, then it is practicing a Catalytic Pedagogy.

In regards to measures: I have created a prototype called the Instant Climate Formative Assessment that you can use with students and/or teachers.

Find out more at HolisticEquity.org/classroom-climate.html

I can also help with advocacy; you can learn more about this at Attitutor.com.

P.S. As a strategic approach to catalyzing a market transformation I have designed a project I call the EDiE Fund. EDiE stands for Experiential Data in Education. The core of the plan is to have philanthropic foundations pay schools to use and disseminate agency data over a ten year period. The fund will pay for an additional dedicated staff person in the first year and over the course of ten years the annual grant decreases 10% with the expectation that the school will replace those funds through other mechanisms (tuition, increased fund-raising, etc.) in order to maintain the data flow and the staff position. The idea is to get the agency data flowing quickly at the same time that the capacity for using and disseminating the data is being built within the school organization. The long timeline also avoids a funding cliff for the school that might jeopardize the data flow.

References

- Feynman, R., & Leighton, R. (contributor). (1985) Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!: Adventures of a Curious Character, W. W. Norton, ISBN 0-393-01921-7

- Gray, P. (2013). Free to Learn. Basic Books. pp. 14-16

- Harter, J. (2017, December 20). Dismal employee engagement is a sign of global mismanagement. Retrieved March 03, 2018, from http://news.gallup.com/opinion/ gallup/224012/dismal-employee-engagement-sign-global-mismanagement.aspx

- Heath, D. (2020). Upstream: The Quest To Solve Problems Before They Happen. Avid Reader Press.

- Mackay, C. (1841, 1972). Extraordinary popular delusions and the madness of crowds. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- McLean, B., & Elkind, P. (2003). The smartest guys in the room: The amazing rise and scandalous fall of Enron. Portfolio.

- Lewis, M. M. (1989). Liar’s poker: Rising through the wreckage of Salomon Brothers. Norton.

- Lewis, M. (2004). Moneyball: The art of winning an unfair game. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

- Lewis, M. (2006). The Blind Side: Evolution of a game. W.W. Norton.

- Lewis, M. (2010). The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine. W.W. Norton & Company.

- Rose, T. (2016). The End of Average: Unlocking Our Potential by Embracing What Makes Us Different. HarperCollins Publishers.

- Tinsley, C. H., Dillon, R. L., & Madsen, P. M. (2011). How to avoid catastrophe. Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://hbr.org/2011/04/how-to-avoid-catastrophe.

This article was printed from HolisticEquity.com