Holistic Education:

Overcoming the Exclusion Delusion in Schools

When you hear the phrase holistic education, what comes to mind?

For some, the phrase conjures up the idea of a transcendent spiritual journey—something ultimately ineffable and beyond scientific scrutiny.

While that is a poetic sentiment, I don’t believe that view is widespread.

Most of us believe education is amenable to scientific scrutiny.

But this raises a difficult question: If education can be analyzed scientifically, why is it so difficult to manage?

Why does the political pendulum of school reform swing so wildly back and forth?

And most importantly, does holistic education have something practical to offer to stop this chaotic swinging?

The answer is yes. But to get there, we must understand that integrating a variety of viewpoints is the defining characteristic of holism.

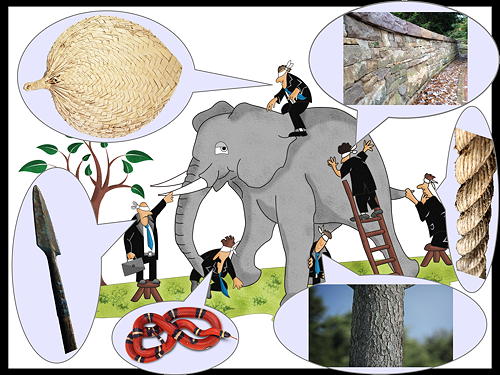

The Blind Men and the Elephant

To understand why education debates are so polarized, we have to look at how humans perceive truth.

All sides in the education debate usually get at least one thing right, but they get a lot of other things wrong.

The differences become irreconcilable only when we insist that our view is the only view.

This problem was perfectly captured in John Godfrey Saxe’s famous 1872 poem, "The Blind Men and the Elephant."

In the poem, six blind men approach an elephant.

The first falls against the side and claims the elephant is a wall.

The second feels the tusk and claims it is a spear.

The third holds the trunk and calls it a snake.

The fourth feels the knee and calls it a tree.

The fifth touches the ear and calls it a fan.

The sixth grabs the tail and claims the elephant is a rope.

And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong!

This poem is a distillation of the fundamental human challenge: the conflict between taking a perspective and having perfect objectivity.

The Exclusion Delusion

Let’s modernize this fable to see how it applies to holistic education.

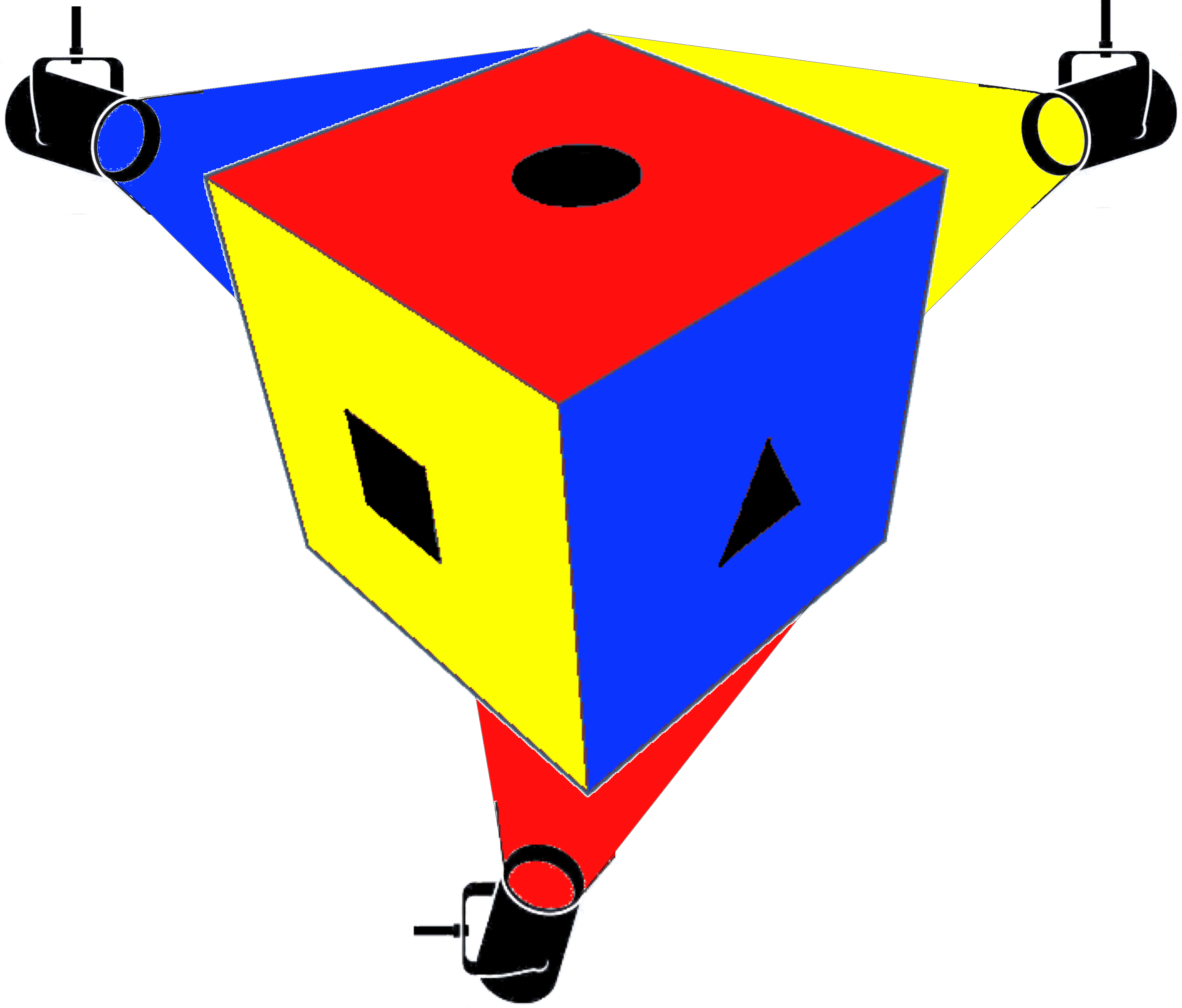

Imagine a hidden object casting three different shadows.

We have three scientists observing these shadows: Isaac Newton, Bill Nye, and Neil deGrasse Tyson.

Newton observes the shadow made by the red light (below) and proposes the object is a sphere.

Nye looks from his angle where he sees the blue field and proposes it is a pyramid.

Tyson sees the yellow field and declares it to be a cube.

They have each made true observations.

Yet, if they conclude that the object is merely a sphere, pyramid, or cube, they have arrived at false conclusions.

If they were politicians, they would attack one another.

But as scientists, their job is to reconcile these observations to understand the complex, three-dimensional reality casting those shadows.

In the realm of schooling, we suffer from what I call the "Exclusion Delusion."

This is the belief that one true observation excludes the validity of others.

When we look at a living child, we are looking at something infinitely more complex than a geometric shape.

We can never be sure we have a final, complete understanding of a living being.

Therefore, relying on a single metric or viewpoint is not just limiting; it is delusional.

Holistic education is the antidote to this delusion.

It requires us to look at the three crucial aspects of the system—learning, teaching, and schooling—without excluding valid truths.

Conceptions of Learning in Holistic Education

What does it mean to learn? Research by John Hattie and Nola Purdie reveals that there are six distinct conceptions of learning:

- Gaining information.

- Personal change.

- Remembering, understanding, and using information.

- Development of social competence.

- Learning as unbound by time and space.

- The duty to learn (prevalent in Eastern societies).

The Exclusion Delusion occurs when public policy assumes only one or two of these are valid.

If a school system acts as if learning is only about gaining and remembering information, the result is shallow learning.

Holistic education accepts the validity of all six conceptions, leading to the deeper learning necessary in today’s world.

Conceptions of Teaching in Holistic Education

Similarly, researcher Daniel Pratt cataloged five ways of conceiving teaching:

- Delivery.

- Nurturing.

- Transformative.

- Immersion.

- Social influence.

The typical delusion in modern policy is that a teacher’s job is limited to the "nurturing delivery" of knowledge.

We often romanticize the "schoolhouse on the prairie" model—a teacher delivering the 3Rs with a stick and chalk.

When political power enforces this oversimplified view to the exclusion of others, the results are disastrous.

When we honor all conceptions of teaching, we arrive at what I call a Catalytic Pedagogy.

This is a teaching method where both teachers and students are internally motivated and engaged agentically, not just behaviorally.

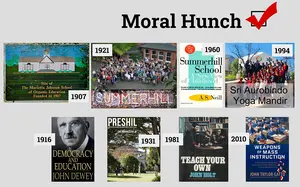

Conceptions of Schooling: The Three Shadows

Finally, let’s look at schooling itself.

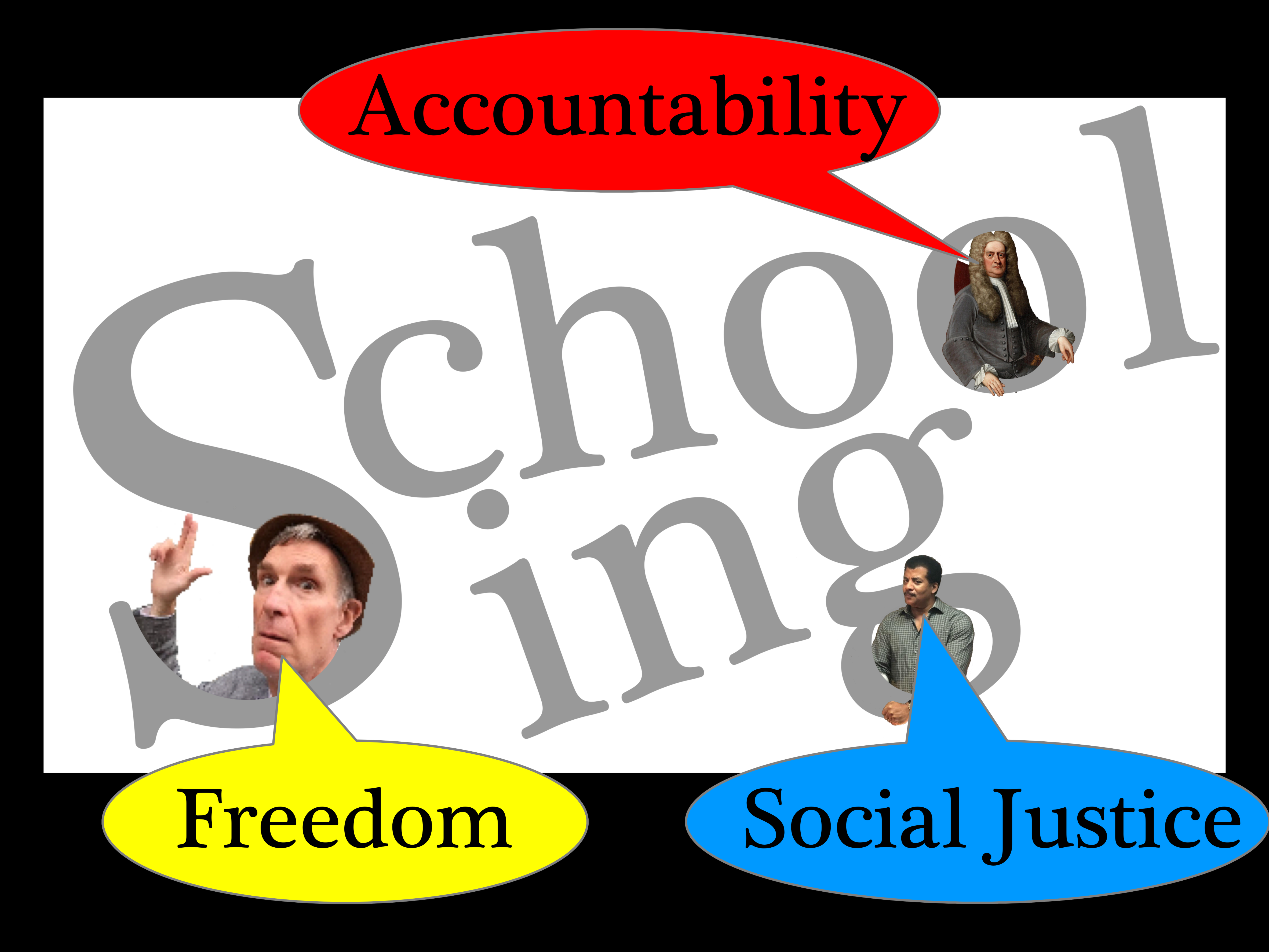

We can map our three scientists to the three dominant views of what schools should be.

The Mainstream View (Newton): Focuses on Accountability. Like Newton’s mechanical universe, this view sees schools as systems to be measured.

The Social Justice View (Tyson): Focuses on Equity. This view recognizes the systemic marginalization of groups and seeks to remedy it.

The Democratic View (Nye): Focuses on Freedom. Champions of this view, like psychologist Peter Gray, argue that mainstream schooling is incompatible with human liberty.

Currently, these groups are fighting a war of mutual exclusivity.

The mainstream erodes freedom-based schools via funding restrictions.

Social justice advocates critique the mainstream’s blindness to inequality.

However, a holistic education perspective seeks the core truth beneath each view.

These truths correspond to the primary psychological needs identified by Self-Determination Theory:

- Competence (Accountability): The mainstream is right that humans have a need to be competent—to be effective agents in their community. However, this is currently distorted by "academic bookkeeping" (grades and test scores) rather than actual mastery.

- Relatedness (Social Justice): The social justice view is anchored in the need for relatedness—the need to belong. Isolation and fragmentation harm everyone, not just marginalized groups. Gallup data shows 70-85% of the global workforce is disengaged, a sign of pervasive psychological harm.

- Autonomy (Freedom): The freedom view highlights the need for autonomy—the need to perceive oneself as the cause of one’s own actions.

The Path to Holistic Equity

So, what lies at the center of the Venn diagram where these three views overlap?

That center is Holistic Equity.

We cannot have a successful education system if we only focus on accountability (competence) while ignoring the need for belonging (relatedness) and freedom (autonomy).

The Exclusion Delusion forces us to pick a side, but the child needs all three.

My strategic plan for schools, which I call Back-to-Basics 2.0, aims to help schools become "Attitutor Schools."

These are schools that utilize Catalytic Pedagogy to ensure that the primary psychological needs of all humans in the system—students and teachers alike—are met.

I use the term holistic education not to describe something mystical, but to describe a system that is rigorous enough to include the whole human being.

We must weave these partial truths together.

It is the only way to stop the pendulum from swinging and start making a real difference for our children.

If you would like to keep up with how we are building this reality, please sign up for the newsletter.

Resources:

Purdie, N., & Hattie, J. (2002). Assessing Students' Conceptions of Learning. Australian Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, 2, 17–32.

Pratt, D. D., Arseneau, R., Boldt, A., Johnson, J., Nesbit, T., Rodenburg, D., & T'Kenye, C. (2005). Five Perspectives on Teaching in Adult and Higher Education. Krieger Publishing Company.

Prototype Assessment System: Classroom Climate Formative Assessment Tool

Video: What is a holistic approach to education?

Video: Introducing Catalytic Pedagogy:

Better Schooling for More Children

Peter Gray's essay on the impossibility of reform and the necessity of outside revolution in education

Peter Gray's study of Sudbury Valley School: Gray, P., & Chanoff, D. (1986). Democratic Schooling: What Happens to Young People Who Have Charge of Their Own Education? American Journal of Education, 94(2), 182–213. https://doi.org/http://www.jstor.org/stable/1084948

This article was printed from HolisticEquity.com