Is Student Choice The Magic Bullet? Education Hygiene Ep. 4

Student choice.

How much choice should we give students?

If they’re gonna make childish choices, shouldn’t we prevent that?

Despite what some may think, student choice is neither good nor bad, so stick around to explore what the science has found.

Welcome to the Education Hygiene Series in which I will be explaining the specific teacher behaviors that scientists have found influence student motivation for better … and for worse.

Episode Links:

Series Links:

Survey- Teachers’ Effects on Student Motivation

Introduction to the Education Hygiene Series

Source: Ahmadi, A., Noetel, M., Parker, P. D., Ryan, R., Ntoumanis, N., Reeve, J., … Lonsdale, C. (2022, February 4). A Classification System for Teachers’ Motivational Behaviours Recommended in Self-Determination Theory Interventions. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/4vrym

In today’s episode we are talking about student choice.

The consensus paper from motivation psychologists mentions choice in one of the two items that I am focusing on today.

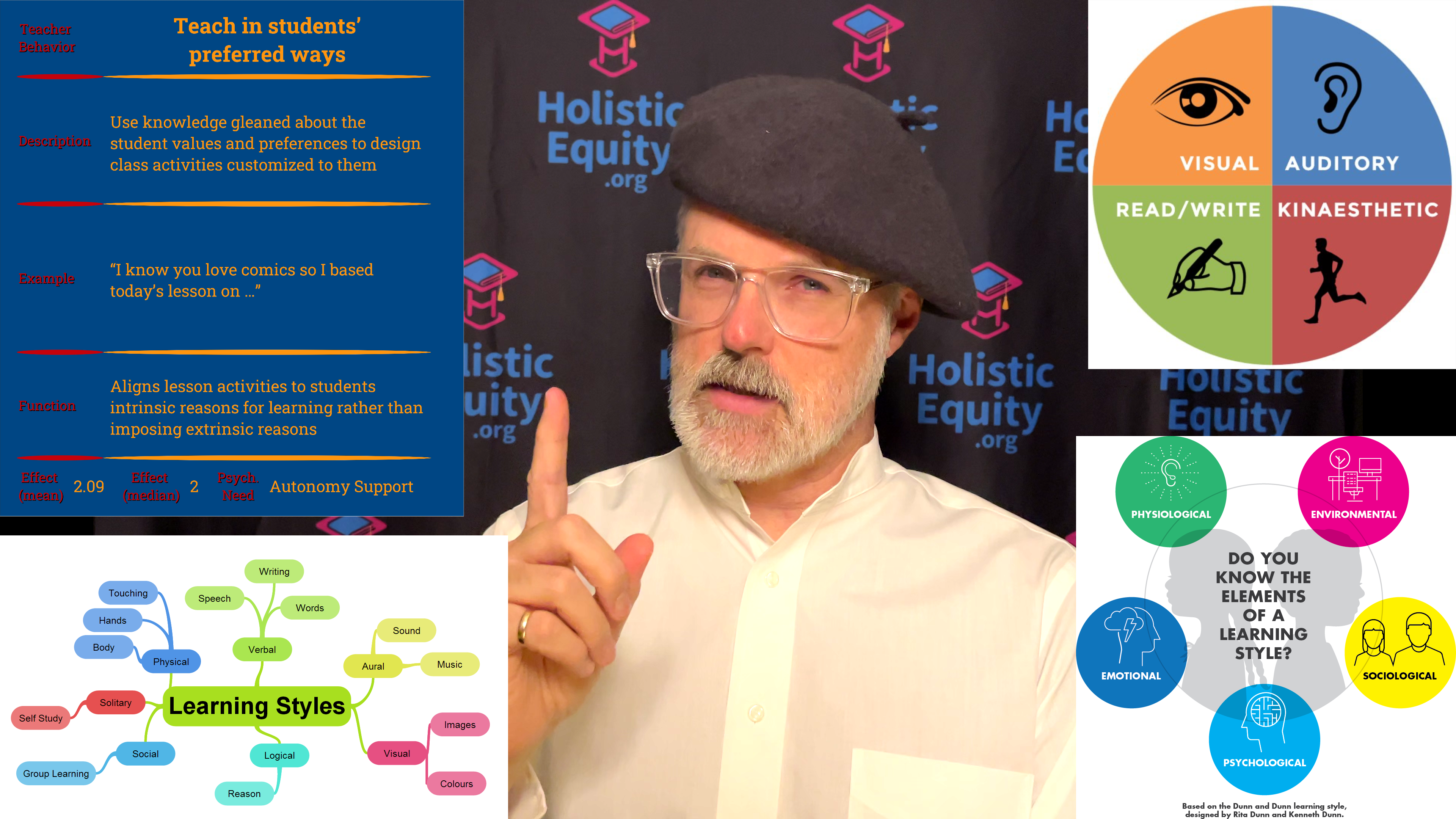

First, before we deal with choice directly, we see the admonition to teach students in their preferred ways.

Preferences as Student Choice

If it is based on their preference, doesn’t that basically mean that we are supposed to teach in a manner of their choosing?

Some might see this as justification for matching preferred learning styles to teaching practices.

However, learning styles are irrelevant to teaching.

The psychological findings do NOT obligate a teacher to concern themselves with so-called “learning styles.”

What the psychologists focus on is obligating teachers to attend to the values and preferences of their students in regards to the activities that make up the learning experiences that the teacher is facilitating.

The most effective teacher’s will pay close attention to whatever intrinsic reasons for learning are driving a student’s behavior.

Student’s come from unique situations that land them in front of that teacher, in that class, in that moment.

The more teachers take that larger context of the student’s life into account the more effective they will be.

Taking advantage of the intrinsic motivations is wise while imposing extrinsic motivations on students is inherently counter-productive to any teacher’s educative goals.

Considerations in Student Choice

Shifting to the second item, let’s resolve an apparent conflict that can arise when we talk about student choice.

There are some folks who would enshrine student choice as a sacred value such that students should make as many choices as humanly possible.

On the other hand, since children are rarely ever given any meaningful choices over their own activities the mainstream of schooling appears to regard student choice as effectively irrelevant to learning.

This point is supported by the very existence of bathroom passes.

Thus, the tension between the student choice as sacred value perspective and the choicelessness of mainstream schools presents a clear conflict.

Here is a quote from the late Daniel Greenberg who was one of the co-founders of Sudbury Valley School and might have be considered a champion of the student choice as sacred perspective.

Quote

“Everyone praises [the basic virtue of responsibility], and every school seeks to inculcate a sense of responsibility in its students.

“Adults carry on about the importance of teaching children to behave responsibly, and educators follow suit by trying to instill such behavior from an early age.

“The problem arises from a basic misunderstanding about what the term means.

“Here’s how the American Heritage dictionary defines “responsible”:

“‘Involving personal accountability or ability to act without guidance or superior authority.’

“The whole point of this virtue is the exercise of personal choice in an ethical situation, where one has the freedom to act in a number of different ways.

“Thus, for example, we call parents responsible if they perform caring acts towards their children, as opposed to letting their children go hungry, or be poorly clothed, etc.

“A parent is not considered to behave responsibly if s/he only provides for their children under a court order, under the threat of a fine or imprisonment if they should fail to do so.

“What do our schools do with this concept?

“They turn it upside down!

“Children are assigned tasks – homework, in-school projects, whatever – under the threat of punishment if they do not fulfill these tasks (a poor grade, or detention, or repeating the course), and then they are considered to be acting responsibly if they perform these tasks according to the required specifications!

“You hear it all the time: a student model of responsibility is one who performs as told; the fact that this is done under coercion is ignored, as if it made no difference.”

End quote.

Here we have a seemingly straight forward statement about the situation of schooling in which the lack of choice-making by students is logically seen as a recipe for irresponsibility.

You might have noticed that I said “SEEMINGLY straight forward.”

Greenberg’s argument rests upon the implicit assumption that the coerciveness of the situation is objectively true.

However, from a psychological point of view the coerciveness of the situation is NOT objectively determined.

Coerciveness only exists as a subjective by-product of how the person perceives their situation.

This means that in the proverbial gun to the head situation, IF the child trusts the adult asking them to behave in a particular way, then the child’s decision to obey the adult’s instruction was based on the trust, not on the basis of the objectively present threat of being shot.

If they don’t perceive coercion, then there is no coercion present.

In most schools when you look at a room full of first or second graders after the first week you will not see any objective evidence of coercion.

First and second graders in mainstream schools are neither at choice nor, Greenberg’s assertion to the contrary, are they being coerced.

Let’s be clear that choice in the consensus paper from the psychologists is presented as one way in which student input can be incorporated into the classroom.

Choice is NOT ALWAYS necessary.

Choices made by trusted others on behalf of the student will be perfectly acceptable from a psychological point of view.

Notice that the key qualifier in front of the word teacher in that last sentence is “trusted.”

If there is not sufficient trust, then that will be a problem.

The key to understanding the role of who chooses is that children will gladly accept the choices made by people THEY TRUST, and it just happens to be the case that they usually trust themselves more than they trust anyone else.

Another key element of understanding the role of choices is that they must be meaningful.

Research has clarified that meaningfulness is entirely derived from psychological need support.

When making a choice occurs within the context of a student having their needs for relatedness, autonomy, and competence supported, then the choice is going to be inherently meaningful.

Greenberg’s point about responsibility is well made, but just giving students every possible choice is not going to get us there.

To be precise, they need to make only as many choices as are consistent with the support of their primary psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

And to be clear the satisfaction of those needs, like the presence of coercion, is subjective not objective.

If the child perceives his or her needs to be satisfied, then they are satisfied, no matter what the objective facts of the situation are.

That is why first and second graders do not show objective signs of coercion.

As long as they still trust their teachers, then they are accepting that those teachers are making good decisions on their behalf.

Unfortunately, a substantial body of research has found that motivation and engagement consistently decline throughout all the years from Kindergarten through twelfth grade.

That evidence suggests that most of the students have unconsciously realized that they were wrong to trust their teachers.

So, choice is a good option for taking preferences into account, but it is not, in itself, enough to reliably produce educative outcomes.

Outro

I invite you to visit Holistic Equity.org to explore more topics about school reform from a psychological point of view.

I also invite you to share your thoughts about this video by clicking on the Contact link.

On the site you can also find out about my book Schooling for Holistic Equity: How to Manage the Hidden Curriculum in K-12.

Finally, if you follow the links underneath this video you can find out how much you already know about Teachers' Effects on Student Motivation because I created a survey where you can compare what psychologists have found to your knowledge of motivation.

Thanks for watching.

This article was printed from HolisticEquity.com