Deconstructing the Engagement Myth: Why Intuition Fails in Classrooms

The ASCD Educational Leadership Magazine holds a prestigious position in the world of education, yet in 2021 they were perpetuating an engagement myth.

In their "Show & Tell" column titled "New Thinking About Student Engagement," authors Fisher and Fry argue that the established 3-part model of engagement (presented by Appleton et al. in 2008) is insufficient for guiding teachers today.

While they were correct that the older model required updates based on a decade of new research, their proposed solution was problematic.

They advocated for a model that was neither designed to nor intended to replace empirical research.

To truly serve students and deliver on educational outcomes, we must look past the engagement myth and toward a model derived from Self-Determination Theory (SDT).

The Origins of the Engagement Myth

The model Fisher and Fry advocated was published in 2020 by Amy Berry. It is crucial to understand the context of Berry’s work to see where the engagement myth takes root.

Berry’s model was derived from interviews with fifteen upper elementary teachers in Australia.

Her research method was not intended to define the objective scientific phenomenon of engagement.

Rather, it was designed to capture what teachers perceive and express as the truth about engagement—flaws and all.

Berry explicitly stated that her model should not be used to replace existing empirically supported models.

Unfortunately, by ignoring this caveat, Fisher and Fry elevated a descriptive model of teacher intuition to the status of a prescriptive guide.

This created a dangerous engagement myth: the idea that teacher intuition alone is a sufficient metric for evaluating student psychology.

The Problem with the Intuitive Continuum

Why is relying on an intuitive continuum dangerous? While it accurately reflects how teachers feel about engagement, it fails to account for the internal psychological states of students.

Using such an intuitive continuum often leads to subtle biases toward teacher-centric, compliance-oriented practices.

Hidden inside this engagement myth is the assumption that the only relevant goals in a classroom are those defined by the teacher’s instructional agenda.

If we accept that education has moved past strict compliance pedagogy, we must reject models that reinforce it.

The Engagement Myth in Practice: A Case Study

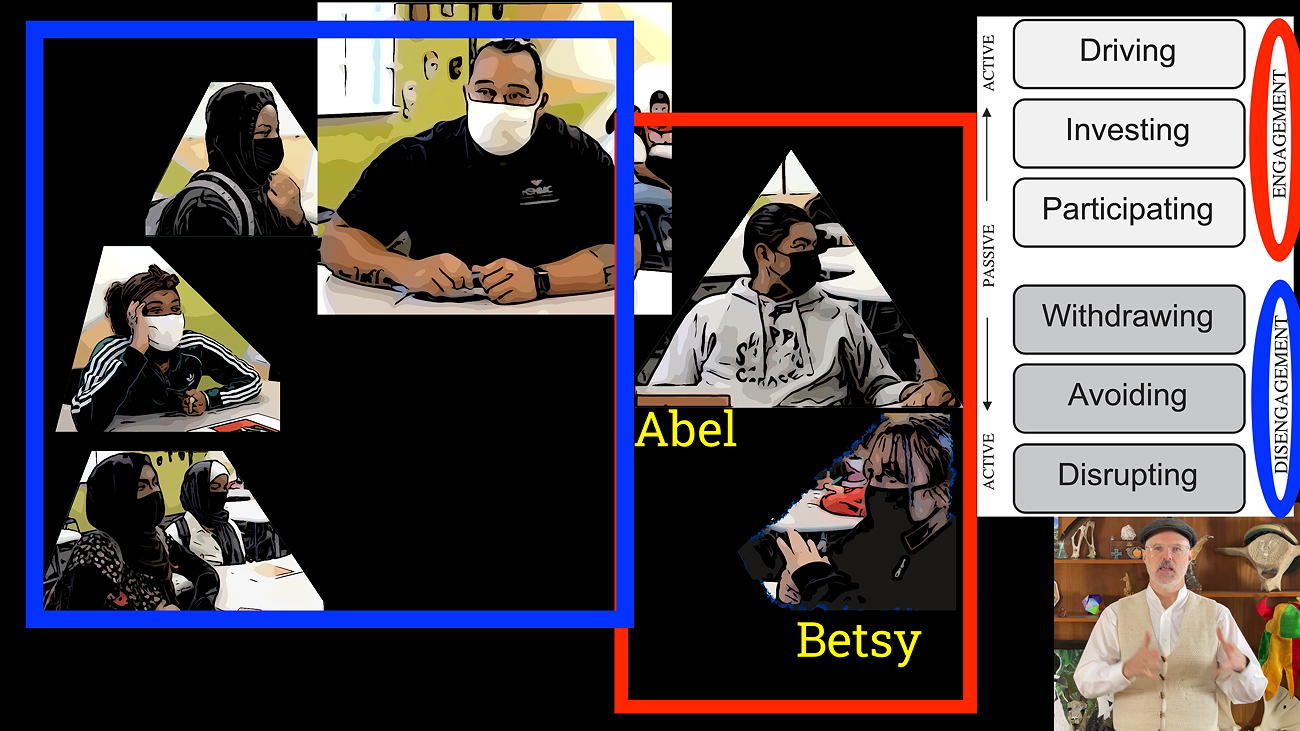

To illustrate the dangers of this continuum, let us look at an imaginary version of Mr. Tutogi’s history class (the teacher featured in the video Fisher and Fry shared).

Imagine two students, Abel and Betsy, exhibiting behaviors labeled as "disrupting" and "avoiding"—the two "worst" forms of disengagement on Berry's continuum.

Under the influence of the engagement myth, the class and teacher would negatively evaluate these students. They are set up to be corrected.

However, this assessment ignores agency.

From an SDT perspective agency is the result of motivations being autonomous; this indicates that primary psychological needs for autonomy, competence, relatedness are being satisfied.

The technical phrase is “agentic engagement” which means the learner is putting their ideas, emotions, and identities into the learning situation.

The opposite occurs when primary psychological needs are thwarted; leading to motivations being controlled and the person engaging in only the behavior without their personal investment.

- Lack of Consensus: If the teacher has not established a classroom consensus where students agree to participation goals, Abel and Betsy are being punished for violating expectations they never agreed to.

- Thwarted Needs: Lack of agency indicates that primary psychological needs have been thwarted, or at least neglected. If the school environment does not support these needs, students will act according to biological imperatives to satisfy them.

If a student’s primary needs are not met, their non-conscious mind will negate their commitment to the teacher's explicit goals.

Science vs. The Engagement Myth

This is where the engagement myth crumbles against the weight of scientific evidence. Self-Determination Theory posits that primary need satisfaction is a necessary prerequisite to autonomous motivation and agentic engagement.

If Mr. Tutogi uses only the intuitive model, he lacks the frame of reference to see that Abel and Betsy are actually highly engaged.

They are engaged in the pursuit of their own biological meta-goals: satisfying their psychological needs.

- From the Teacher's Perspective: The behavior is "disrupting" the lesson.

- From the Student's Perspective: The behavior is "engaging" in self-preservation and need satisfaction.

The same behavior can be legitimately viewed as both engaged and disengaged simultaneously, depending on the goal being pursued.

The engagement myth fails because it only measures behavior against the teacher's goals, ignoring the student's implicit meta-goals.

Breaking the Illusion

Jennifer Fredricks, a leading researcher, noted in her book Eight Myths of Student Engagement that the first myth is: "It’s Easy to Tell Who Is Engaged."

Fisher and Fry claim the intuitive continuum helps teachers gauge engagement "more precisely."

In reality, this reinforces the engagement myth that observation equals understanding.

To be more accurate, the intuitive continuum helps teachers gauge how much students are subjugating themselves to instructional demands.

While trusting a teacher and following their lead is positive, it must be based on earned trust and need support.

If a teacher demands conformity without supporting well-being, they are undermining the student's ability to learn deeply.

Leadership Over Illusion

To move beyond the engagement myth, educators must adopt a leadership role that understands the causal chain of learning:

- Environment: Provides support.

- Needs: Primary needs (relatedness, autonomy, competence) must be satisfied.

- Motivation & Engagement: These flow downstream from need satisfaction.

- Learning: The result of the interaction.

Goals act as meta-cognition influencing this chain. Primary needs are implicit meta-goals that operate 24/7 in the background.

If a teacher’s explicit goal contradicts a student’s implicit needs for autonomy, competence, and/or relatedness, the student will sacrifice the teacher's goal to satisfy the internal need.

The secret to effective intervention is not correcting behavior (the symptom), but supporting primary needs (the cause).

When educators focus on Relatedness, Autonomy, and Competence, engagement usually takes care of itself.

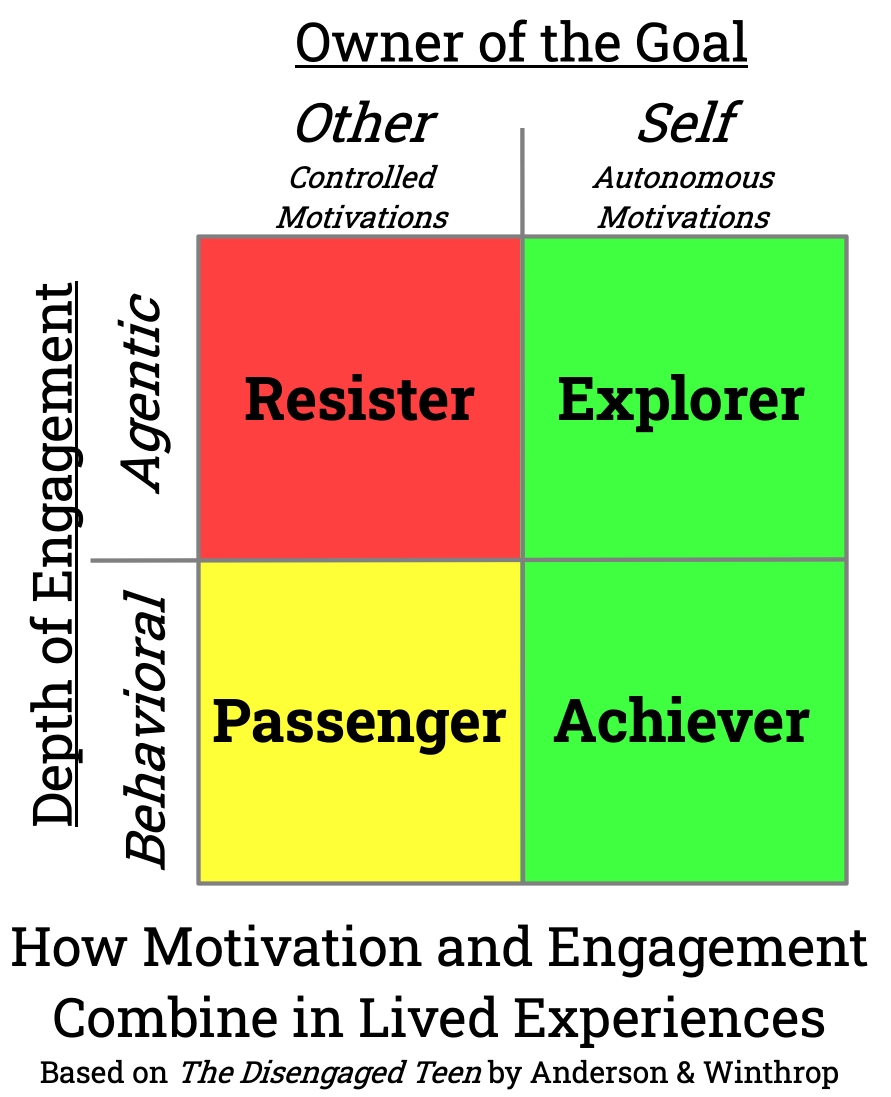

Inspired by Anderson and Winthrop’s recent book The Disengaged Teen I created a table to show how motivation and engagement combine to become lived experiences for students.

The first distinction at the top is who owns the goal, the student or the teacher.

If the goal is owned by the teacher (other) but not the student (self) then that results in controlled motivations for the student.

If the goal is owned by both the student and the teacher the result is autonomous motivation for the student.

The second distinction is the degree of engagement.

If the student invests their identity in the activities the result is either exploration when they have autonomous motivations or resistance when they have controlled motivations.

If the student withholds their identity from the activities the result is either pursuing achievement when they share the goals of their teacher or being a passenger when they do not share the goal.

Conclusion

It is ironic that the same issue of Educational Leadership features an article titled "The Engagement Illusion," warning that direct observation is insufficient.

Yet, by promoting Berry's intuitive model as a replacement for scientific frameworks, Fisher and Fry inadvertently feed the engagement myth.

Teachers should be encouraged to update their intuitions based on science, not validate intuitions that harbor misunderstandings.

While the older 3-part model of engagement needed updating, replacing it with a model based on teacher perception is a step backward.

To truly deliver for our students, we must look at the larger picture painted by Self-Determination Theory.

We must recognize that "bad" behavior is often a student's attempt to satisfy a thwarted need.

By moving past the engagement myth and focusing on the invisible aspects of deep learning, we can create classrooms where engagement is authentic, not just compliant.

For more information on bridging the student engagement gap, visit `HolisticEquity.org/student-engagement.html`.

To explore the larger picture of equity and engagement, visit `HolisticEquity.org` and sign up for the newsletter.

Resources

- Anderson, J., & Winthrop, R. (2025). The Disengaged Teen: Helping Kids Learn Better, Feel Better, and Live Better. Crown.

- Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., & Furlong, M. J. (2008). Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 369–386.

- Berry, A. (2020). Disrupting to driving: Exploring upper primary teachers' perspectives on student engagement. Teachers and Teaching, 26(2), 145–165.

- Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2021, December). Show & Tell: A Video Column / New Thinking About Student Engagement. ASCD Educational Leadership, 79(4), 76–77.

- Gupta, N., & Reeves, D. B. (2021, December). The Engagement Illusion. ASCD Educational Leadership, 79(4), 58–62.

- Fredricks, J. A. (2014). Eight myths of student disengagement: Creating Classrooms of Deep Learning. Corwin.

SDT Articles about Primary (a.k.a. Basic) Needs & Agentic Engagement:

- Martela, F. (2020). Apes in tuxedos: Robust sense of meaning built upon our evolutionarily developed basic psychological needs. Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture, 4(1), 35-38.

- Montenegro, A. (2017). Understanding the Concept of Agentic Engagement for Learning. Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 19(1), pp. 117-128.

- Reeve, J., & Tseng, C.M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(4), 257–267. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.05.002

This article was printed from HolisticEquity.com