Direct Instruction Treats a Symptom, Not The Disease

Is direct instruction a necessity for learning biologically secondary knowledge? I think not.

There is a popular notion that reading and writing are categorized as biologically secondary knowledge.

It was originally proposed by David Geary and reasserted by John Sweller, “[C]ognitive load theory has been applied exclusively to the acquisition of biologically secondary subject matter taught in educational and training contexts.

That subject matter, like all biologically secondary information, requires explicit instruction and a conscious effort by learners.” (Paas & Sweller, 2011)

As such children require explicit or direct instruction from knowledgeable adults to reduce the cognitive load that would otherwise be required to learn that knowledge through other forms of instruction.

That assertion also happens to reinforce the harmful mainstream assumption that adults must be in control of children’s learning.

I agree that reading and writing are evolutionarily new skills, but I also assert that it is a trivial, unimportant fact.

The notion that learning evolutionarily new skills requires adult intervention, specifically direct instruction, requires assumptions about children’s motivation and engagement that contradict the most successful scientific account of human motivation and engagement today, Self-Determination Theory.

There is good reason that direct instruction appears successful in mainstream schools, but that is because the mainstream is afflicted with an institutional disease that routinely causes the psychological needs of both children and their teachers to be routinely thwarted and/or neglected.

The disease that direct instruction cannot cure and, in some cases makes worse, is the thwarting and/or neglecting of psychological needs.

Four key points: First, motivation has a major impact on learning, so explaining a bit of Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is necessary.

Second, I will explore what “natural” learning means based on the science of SDT.

Third, I will point out that mainstream schooling creates an un-natural situation for learning.

Finally, the perceived benefits of direct instruction are contingent on that environment, not the evolutionary birth order of the knowledge being taught.

Therefore, direct instruction is, at best, treating a symptom of the disease that is afflicting mainstream schooling; at worst it exacerbates the disease.

Learning and Self-Determination Theory

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is based on the observation that all humans, but children especially, are inherently curious, except when situational factors dampen that curiosity.

Children, in particular, are biologically driven to become competent members of their society, according to psychologist Peter Gray (2019).

The human learning system is driven internally by motivation and expresses itself in the world through engagement.

Knowledge is built through mental processes that are motivated by psychological need satisfaction.

Knowledge building also requires behavioral processes that are engaged with the social world in which the learner is embedded.

But, according to SDT, not all motivation and engagement is created equal with regard to learning.

From the perspective of psychology, learning happens as long as a human is awake and alive.

But the default is shallow learning which boils down to the assumption that the learners’ current mental models of reality are good enough.

This is why STEM subjects are notoriously difficult to teach effectively.

Shallow learning processes do add information to the existing models and/or generate associations between bits of information that already exist within those current models.

In order to learn deeply a learner needs

1) to be exposed repeatedly to relevant information that does NOT fit their existing models,

2) to get meaningful feedback about that disconfirming information, and

3) to achieve a state of open-mindedness that allows the mind to construct a new model to replace the one being abandoned.

That necessary state of open-mindedness is a by-product of the motivation system.

Motivation occurs on a 6-part spectrum but motivation psychologists these days simplify the spectrum down to two parts: autonomous and controlled motivations.

Autonomous motivations have positive effects on well-being while controlled motivations have mostly negative effects on well-being.

The degree of well-being that is generated by the motivation system has an effect on learning due to the fact that it determines the degree of openness of the mind.

Controlled motivations generate defensiveness which is effectively a form of closed-mindedness that prevents learning from being deep.

Autonomous motivations are characterized by curiosity and other forms of open-mindedness that allows learning to become deep, if the situational conditions are supportive of agentic engagement.

Thus, autonomous motivations are a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for deeper learning.

Engagement has two main components: behavioral and agentic.

Behavioral engagement can be a superficial form of participation, while agentic engagement enables learning to be deeper (both cognitive and emotional processes contribute to it).

When children are just going through the motions or jumping thought the hoops, that is behavioral engagement.

Unlike behavioral engagement, agentic engagement is a social process in which the learner puts their identity, opinions, feelings, ideas, and other aspects of themselves into the learning situation in order to get more out of it.

Agentic engagement does not guarantee deeper learning, but if the learning is not agentic then the learning will not be deep.

So, deeper learning can be prevented by controlled motivations, the absence of agentic engagement, and/or low quality feedback (which includes poor instruction).

Natural Learning

The notion that biologically primary knowledge is acquired “naturally” begs the question of what counts as natural learning.

Learning will appear “natural” when the motivations of the learner are autonomous, there is social support for the learner to express agentic engagement, and there is high quality feedback from reality (or a sufficiently realistic simulation of reality) for the learner to break and re-construct his/her mental model of reality.

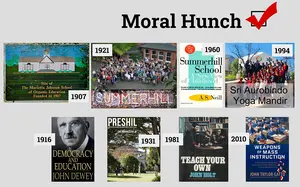

In our evolutionary past, social situations were mostly supportive of autonomous motivations because of their extraordinary egalitarianism (Gray, 2019).

The typical examples given for natural learning are walking and talking. I propose to explain natural learning in terms of conditions that are independent of content knowledge.

It does not matter what language the child is learning to speak, the conditions for that learning to be natural are the same for all humans.

Specifically, natural learning does not depend on the evolutionary birth order of any content knowledge.

Learning to read and write will appear just as “natural” as learning to walk and talk under these conditions.

When homeschooling families and members of other agentic, non-mainstream school communities describe their children naturally learning to read and write with little or no explicit instruction, they are not delusional.

They are simply operating within situational conditions that more closely resemble our ancestral past in which evolution shaped our learning system.

It is the learning situation that is biologically primary, not the content knowledge.

Those children who “naturally” learn to read and write are experiencing social conditions in which their psychological needs are being satisfied, they’re autonmously motivated, and agentically engaged.

Within that situation they recognize that reading and writing are culturally relevant to being a competent member of their society, thus their evolved capacity to learn efficiently and effectively is activated.

If they get good feedback from their environment, which might include direct instruction, that learning will appear to be natural.

Direct Instruction

Instruction is just one way that high quality feedback from reality (or a sufficiently realistic simulation of reality) can be provided.

Direct instruction can be a positive tool for acquiring biologically secondary knowledge, but only when the instructor is operating within a classroom environment that facilitates open-mindedness.

The prevalence of closed-mindedness in a classroom will determine the degree of success or failure of the instructional process independent of the content.

What the direct instruction advocates are correctly observing as hinderances to learning are situations in which the feedback about the reality under consideration is inadequate.

Instructors who neglect to provide adequate knowledge about the reality under consideration are not doing an adequate job of characterizing that reality for learners who lack such knowledge.

Improving the quality of that instruction will improve the situation for those learners whose minds are already sufficiently open to make good use of that higher quality of instruction.

Learners whose minds are closed will fail to benefit from the higher quality of instruction because their patterns of motivation and engagement will prevent them from investing themselves in that opportunity.

If the only form of improvement is instructional quality without any improvement to the social conditions that influence motivation and engagement then the improvements will be limited.

Maximizing the impact of instruction requires more than just improving instructional techniques; it also requires improving the motivational hygiene of that instructor.

Ideally, the maximizing efforts would include improving the social situation, (a.k.a. climate) of the school, too.

It is obvious that instruction, when provided, should be of the highest possible quality.

In order for high quality instruction to be effective it is important that the social situation of schooling facilitate the open-mindedness that is a prerequisite of deep learning.

Schools need to change their central focus from providing instruction to facilitating optimal learning.

Optimal learning does not require instruction, but it does require social facilitation of an environment conducive to open-mindedness.

The deeper disease of mainstream schooling is the institutionalization of unnatural learning situations in which psychological needs are routinely neglected or thwarted.

The assignment of small children to be controlled in large groups with arbitrary bureaucratic enforcement of that assignment (sometimes against the child’s expressed wishes) contributes to the unnaturalness of many classroom situations.

The observed problems with children attaining literacy that direct instruction is meant to address are symptoms of a disease that causes mainstream schools to persistently create un-natural learning environments.

This disease is curable, but not through improvements to instruction.

The disease is curable through aligning the social situations of schooling with natural learning through what I call motivationally hygienic behaviors and agentic schools.

Here is a checklist of motivationally hygienic teacher behaviors.

To learn more about need supportive schools read my latest book The Agentic Schools Manifesto or listen to my vodcast Agentic Schools.

To conclude: Direct instruction is good as far as it goes, but it is not a panacea.

The social situation in which instruction is embedded has a far greater long-term effect than any particular instructional technique.

Motivationally hygienic teaching and appropriate social structuring of the school, such as ensuring only students interested in being instructed are present in instructional situations, are going to be far more powerful factors than any individual instructional technique.

----

P.S. Recent research examining the relationship between Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory and Self-Determination Theory found that they are generally compatible (Evans, et.al., 2024).

Autonomy supportive teaching as recommended by SDT was found to lessen the cognitive load of students.

References

Evans, P., Vansteenkiste, M., Parker, P., Kingsford-Smith, A., & Zhou, S. (2024). Cognitive load theory and its relationships with motivation: A self-determination theory perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 36(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09841-2

Gray, P. (2019). Evolutionary functions of play. The Cambridge Handbook of Play, 84–102. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108131384.006

Paas, F., & Sweller, J. (2011). An evolutionary upgrade of cognitive load theory: Using the Human Motor System and collaboration to support the learning of complex cognitive tasks. Educational Psychology Review, 24(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9179-2

This article was printed from HolisticEquity.com