The Myth of Average:

Schools Require Better Governance, Not Technology

The myth of average has profound implications for how we design systems that serve human beings.

In his TEDx Talk, Todd Rose introduced the concept of "designing to the edges" through a compelling story about Air Force jet fighter pilots crashing at alarming rates in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Understanding the myth of average and its true implications for education requires us to look beyond the obvious solutions.

The Myth of Average Exposed

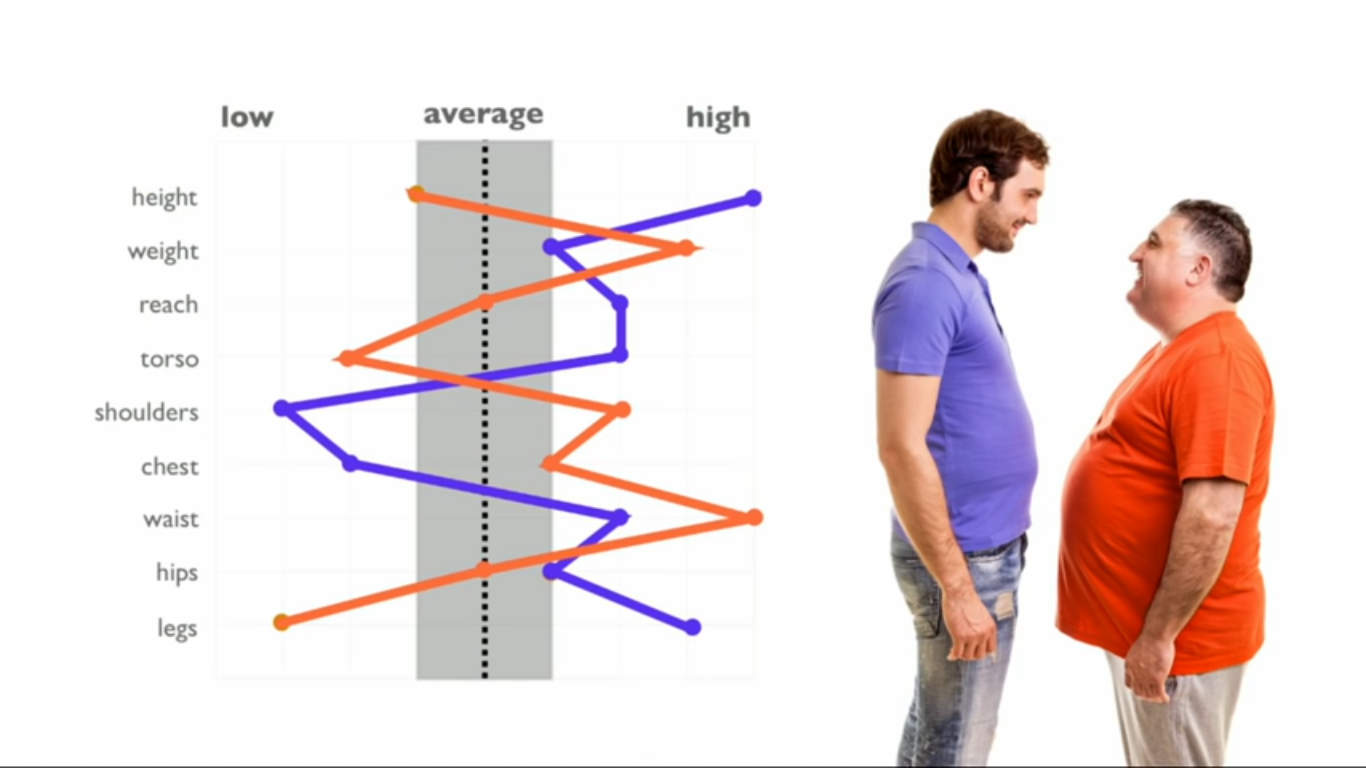

The pilots were crashing because cockpit designers had used outdated specifications based on averages of human body measurements.

These one-size-fits-all cockpits assumed that designing for the "average" pilot would accommodate a "normal" person of average size.

When the Air Force remeasured over 4,000 pilots across ten body dimensions, they assumed that taking the middle 30% of each distribution would identify men within the average range.

How many pilots fit this criteria? Exactly zero.

The myth of average was further exposed seven years earlier when the Cleveland Plain Dealer held a contest to find the "average woman."

A sculptor and gynecologist had created a life-sized statue named Norma based on averages from nine body dimensions measured across 15,000 young women.

Over 3,800 women entered, each considering herself a paragon of normalcy.

When evaluated across all nine dimensions, not a single woman matched.

Researchers had to reduce the criteria to just five dimensions before even 40 contestants qualified.

These stories illuminate a crucial discovery: when you account for six or more dimensions of human variability, no one is average.

The myth of average collapses under scrutiny. No one is "normal" if normal means average.

The Flawed Request from the Myth of Average Talk

Todd Rose's principle of designing to the edges is correct for any endeavor confronting human variability, and education certainly qualifies.

However, in his TEDx Talk—though notably not in his book—he emphasized education technology as the means to achieve necessary flexibility.

He requested that some vague "we" require vendors selling to schools to design to the edges.

This request, while well-intentioned, is not realistic.

The situations of military aircraft procurement and school technology procurement are so different that comparing them borders on nonsense.

The military consists of a handful of branches that each purchase a few hundred planes at a time through centralized decision-making.

In contrast, over 130,000 schools operate across hundreds of jurisdictions in the United States, most making independent purchasing decisions.

This massive decentralization makes coordinating requirements nearly impossible.

Consider the decades of effort required to create the Common Core State Standards.

Despite enormous investment, they failed to produce hoped-for changes and have been abandoned by seven states so far.

The vast difference between how the Air Force buys planes and how hundreds of school bureaucracies buy technology makes Rose's suggestion impractical.

Why Technology Cannot Disrupt Education

Even if coordinated technology purchasing could somehow be achieved, it would not have much effect.

Justin Reich's 2020 book "Failure to Disrupt" makes a compelling case that technology has very specific limitations making it effective for only a narrow range of tasks—none of which are central to education.

Education is properly about how students and teachers interact with each other and with reality.

Technology vendors are irrelevant to these central relationships.

Therefore, it is not even logically plausible for technology to disrupt education except in trivial ways.

Successfully meeting the challenge of designing to the edges in education requires understanding what actually needs to be designed.

The myth of average points us toward human variability, but we must correctly identify where that variability matters most.

Education's Stage of Development

Using Rose's aviation example as a starting point, we must assess what stage of development education currently occupies.

Aviation as we know it had to pass through its Kitty Hawk stage before reaching the Jet Age.

Prior to jets, designers did not need to think twice about human dimensions.

Earlier airplanes were not difficult to fly, so whether pilots fit comfortably in cockpits mattered little.

The designing-to-the-edges work Rose celebrates in his book concerns refining nuances in highly sophisticated aircraft.

For the analogy to apply to education, schooling would need to have reached a similarly high level of sophistication.

Education is closer to the Kitty Hawk stage than the Jet Age.

Evidence of this low sophistication includes the fact that majorities of both teachers and students are disengaged.

Persistent gaps exist in both engagement and achievement between minority and majority students.

Education has not achieved sophistication that could reasonably be called "high."

The Theoretical Foundation We Need

Part of what enabled the Wright brothers to achieve powered flight was the development of aerodynamic principles.

George Cayley developed the concept of the modern fixed-wing aircraft in 1799, identifying the four fundamental forces of flight: lift, thrust, drag, and weight.

This theoretical breakthrough paved the way for the first powered flight in 1903 by enabling Orville and Wilbur Wright to make reasonable predictions about the thrust their aircraft would need.

Education needs a similarly predictive model before the field's sophistication can progress from low to high.

More importantly, we already have that theoretical breakthrough in the form of Self-Determination Theory, even though most educators have not yet recognized it.

Beyond the Myth of Average: Governance Over Academics

With this theoretical foundation in place, we must recognize that education's central concerns are relationship-based, not information-based.

Education is fundamentally about how students and teachers interact with each other and with reality.

If the intuitive notion that education is primarily about information were true, information technology would have become the great disruptor many predicted.

It did not. Jonathan Knee's book "Class Clowns: How the Smartest Investors Lost Billions in Education" provides a thorough account of how wrong Wall Street has been about the education business.

Many prognosticators correctly sense that education is ripe for disruption.

However, the great disruption will not come from technology. It will be based on novel forms of governance.

Our relationships are far more powerfully shaped by social institutions than we normally realize.

Innovations in the governance of teacher-student and student-reality relationships will transform schooling. This is precisely what Self-Determination Theory implies.

The myth of average tells us that human variability must be accommodated.

But the structures needing to be designed to the edges are governance structures, not academic or technological ones.

Reframing the Myth of Average for Education

Todd Rose's analysis exposing the myth of average was valuable.

The problem lies in the premises upon which his educational recommendations were built.

His suggestion about coordinating technology purchasing no longer makes sense once we recognize that education is primarily about how relationships are affected by governance, not how information is delivered.

His book "The End of Average" remains well worth reading because it covers important ground not dependent on the flawed premise from his video.

The myth of average is real and important—we simply must apply its lessons to the right domain.

Helping educators and school policymakers understand how to solve the disengagement problem and close engagement gaps using Self-Determination Theory is essential work.

Equally important is ensuring that innovative governance structures receive the support they need to flourish.

The myth of average teaches us that no one fits neatly into systems that standardize the wrong things.

The solution for education lies not in better technology but in governance structures flexible enough to honor the beautiful variability of every student and teacher.

For a deeper take on education policy read this.

This article was printed from HolisticEquity.com